When NASA announced the single largest finding of planets to date had been discovered, a group of aerospace engineering students at the University of Colorado-Boulder had to pinch themselves.

NASA's Kepler mission recently verified 1,284 new planets, which is the most planets ever discovered in one mission to date.

"A lot of this stuff is rewriting textbooks," Bill Possel, director of mission operations and data systems for the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at CU-Boulder, said.

The Kepler mission started in March of 2009. Over the past few years, the students had a direct role in the mission that made this latest discovery.

Since that moment, CU-Boulder students have been operating the satellite from their mission control center at the LASP on campus.

"It's really exciting to be a part of it to say that I flew satellites during my college career," Charlie LaBonde, an aerospace engineering student at CU-Boulder, said. "That's not something many people can say."

Seventy students through the past seven years, with the supervision of faculty, have had a chance to communicate with and monitor the Kepler mission. All the commands sent to Kepler have been by a student.

"To come out with that finding, that study that 'Hey, there are planets that could harbor life,' and we helped be a part of the team that could have helped find them, it's a mind-blowing experience ... hard to put into words," Rishab Gangopadhyay, an aerospace engineering student at CU-Boulder, said.

Twice a week, the staff and students collect data about the spacecraft health and analyze this data to make sure everything on the spacecraft is working properly.

"They're not only top students, they have the experience and the training to sit in the hot seat -- if you will -- to send the commands," Possel said.

From 2009 to 2014, they collected the data monthly and send it to NASA for analysis. In 2014, they collected it quarterly.

The students don't physically see planets in their mission control room when collecting data, so how does NASA then discover thousands of new planets? Scientists found -- in thousands of instances -- the planet is eclipsing a star.

Here’s what happens: The planet moves in front of a star. There’s a very small change in light which indicates that the dimming could be a planet moving in front of the star.

"It's awesome, it's so exciting to have a small part even of discovering these new planets," Maggie Williams, an aerospace engineering student at CU-Boulder, said. "Even though we're just here down-linking data, we're a part of the big pictures of discovering whole new worlds."

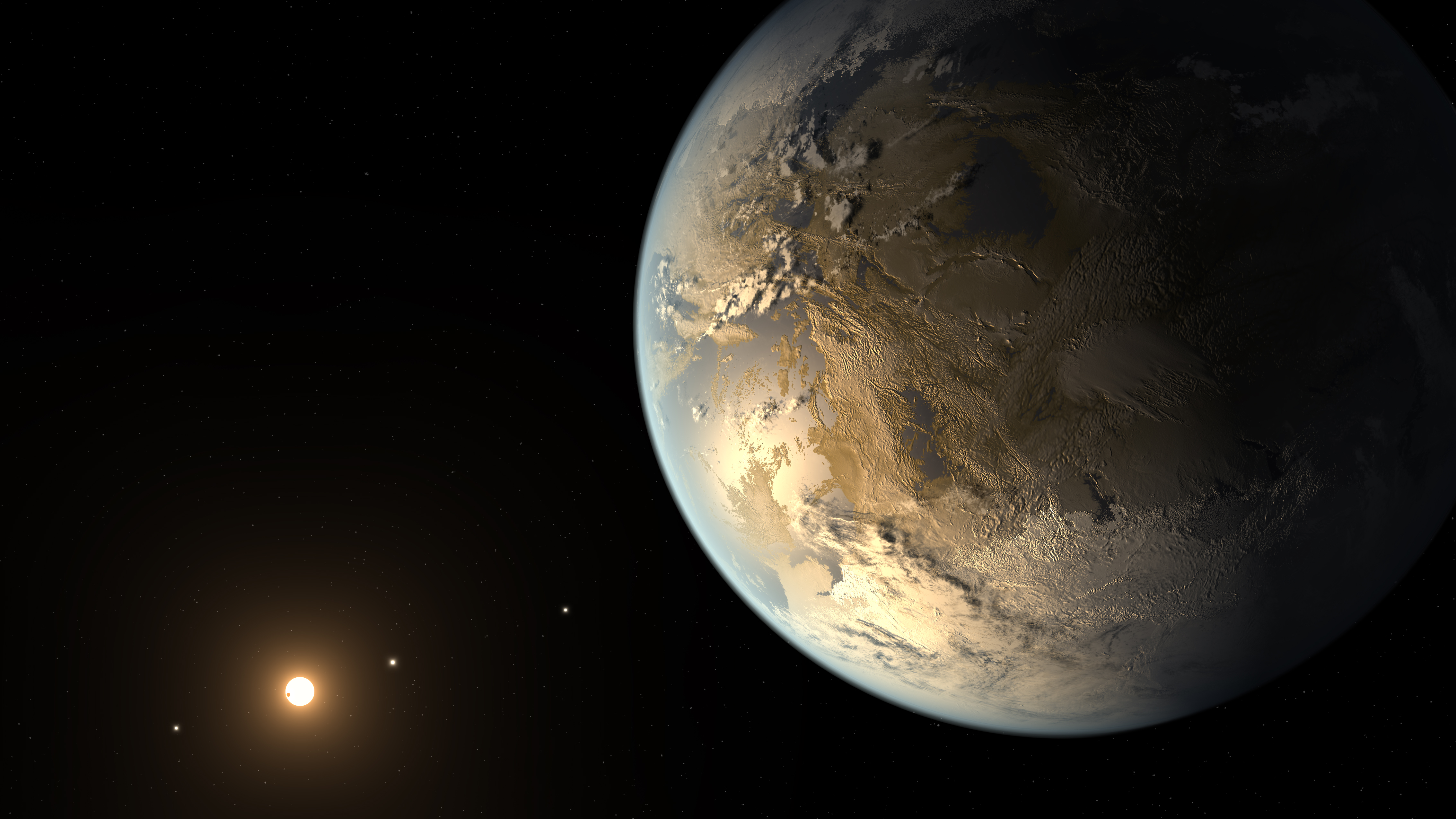

While we haven’t seen the planets and won’t be able to see them, the artist representation above shows an image of what they might look like.

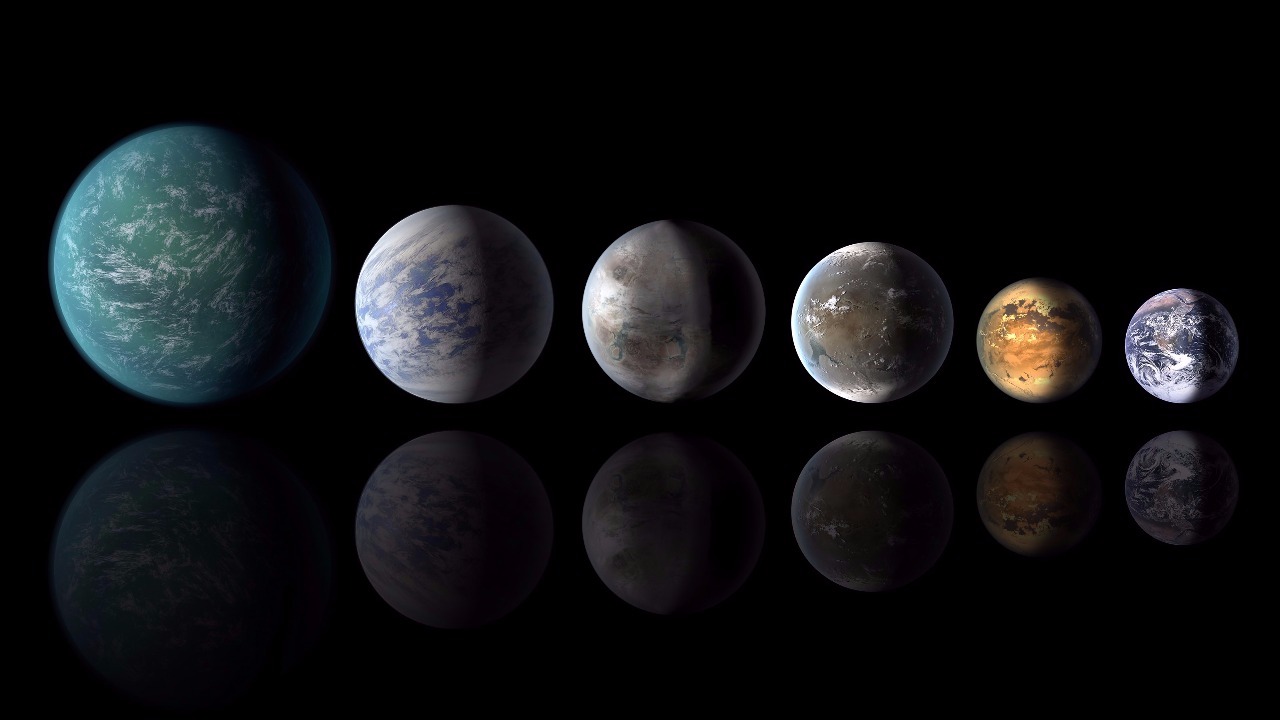

NASA said of the nearly 5,000 total potential planets found to date, more than 3,200 now have been verified.

What’s even more fascinating is 2,325 of them were discovered by Kepler, NASA says Kepler is the first NASA mission to find potentially habitable Earth-size planets.

Ellen Stofan, chief scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said this discovery of planets is critical.

“This gives us hope that somewhere out there, around a star much like ours, we can eventually discover another Earth,” Stofan said.

Of the newly-validated batch of planets, NASA said nearly 550 could be rocky planets like Earth.

Another local connection to the Kepler Mission: Ball Aerospace in Boulder built the Kepler spacecraft. LASP has a contract with Ball to perform the operations.

Before the students at CU-Boulder are considered “qualified” to help operate the satellite, they go through extensive training which includes written and practical exams.

"It's been a fantastic experience," LaBonde said. "There's no other place in the world where I can get this type of experience at. Places have similar programs, but they don't involve their students like we do, and it's a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be here and do what we do."

Students work 20 hours a week during the school year and 40 hours a week in the summer.

When Kepler has technical problems, the students are fully integrated in it with Ball Aerospace engineers. They help in bringing the spacecraft back into operations.