A 9Wants to Know and Rocky Mountain PBS investigation found the 10 most arrested and cited people in Denver cost the city hundreds of thousands of dollars in court costs, jail nights and emergency room visits.

The 10 people, gripped by addiction and living on the street, underscore the devastating cost of homelessness in Denver.

“Me, I drink every day,” said Tyrone Henry, the city’s most arrested and cited man.

A 9Wants to Know analysis of Denver police records show that police ticketed or jailed Henry 64 times from Jan. 1, 2011 to Dec. 31, 2015.

Henry’s life has been a cycle – he’s regularly caught drinking in public, is cited, arrested, taken to jail or detox and released. The cycle repeats again.

“Tried to quit drinking? Never in my life,” Henry told 9Wants to Know. “Oh, no, I always wanted to keep drinking and keep drinking and just having fun man.”

Just 10 people cost the city more than $477,000, according to 9Wants to Know calculations using cost estimates provided by City of Denver finance department for jail, court and police time.

“We spend a lot of money incarcerating these individuals, arresting these individuals,” Lonnie Schaible said, associate professor of Criminal Justice at the University of Colorado Denver. “That takes officers off the street – that prevents them from dealing with bigger problems and issues.”

The top 10 most arrested and cited individuals in Denver spent 3,705 nights in jail from 2011-2015. That’s about $300,000 for jail time alone.

“Folks that are part of this high-user group are not the folks we should be having in jail,” Regi Huerter said, the executive director of Denver’s office of Behavioral Health Strategies.

“They’re dealing addiction issues, they’re dealing with mental health issues,” Huerter said. “And so the last place they should actually be treated is in jail.”

Added costs of detox and ER visits

The majority of arrests and citations for these ten were for alcohol-related crimes. Often, the inmates are also taken to detox or to the emergency room.

Rocky Mountain PBS and 9Wants to Know were given permission by 5 people to examine the costs to the city for emergency room visits and detox with Denver Health and Denver CARES, the community detox facility.

Those five individuals cost taxpayers more than $422,000 for visits to Denver Health and Denver CARES since 2011 – primarily related to alcoholism and injuries.

In all, 9Wants to Know estimates that in 5 years, ten people cost taxpayers more than a million dollars in jail time, court costs, police time, and medical care.

The role of police

“There are a lot of chronic homeless in the city,” said Officer Steven Hammack.

Officer Hammack is a Crisis Intervention Trained officer and works in the homeless outreach unit for DPD.

“I run into those folks quite a bit, because I like to keep tabs on them to make sure they aren’t hurt; they aren’t freezing, they have clothing and food – things like that,” Hammack said.

The police department has been enacting a variety of different strategies to respond to calls for service for people in need, whether homeless or in the midst of a mental health crisis. More and more officers are armed with crisis intervention training, and in addition to the homeless outreach unit, six licensed mental health counselors now join police officers on certain calls for service to help intervene.

“If I can get the entire department to do what I do to a point, it would help us a ton,” Hammack said.

Still, dozens of arrests every year come down to infractions like drinking in public, public urination, trespassing and panhandling – the kinds of infractions that are seemingly inevitable when an individual doesn’t have a private place to call home.

“When you’re homeless on the streets, sometimes that alcohol is actually more available than staying sober and actually may be more attractive,” Huerter said.

New approaches to decades’ old challenge

Now – the city is investing in a major effort to divert this money – provide chronically homeless individuals with permanent housing.

The model is called “Housing First.”

“We’re very specifically targeting those folks who are chronically coming to the system,” Huerter said. “Who are chronically known because of their behaviors, and trying to get them into a different setting.”

The housing units are funded by the “Social Impact Bond,” which is a bond program that allows investors to earn interest if the city saves money on housing certain chronically homeless individuals rather than continuing the cycle of arrest, jail, release and repeat.

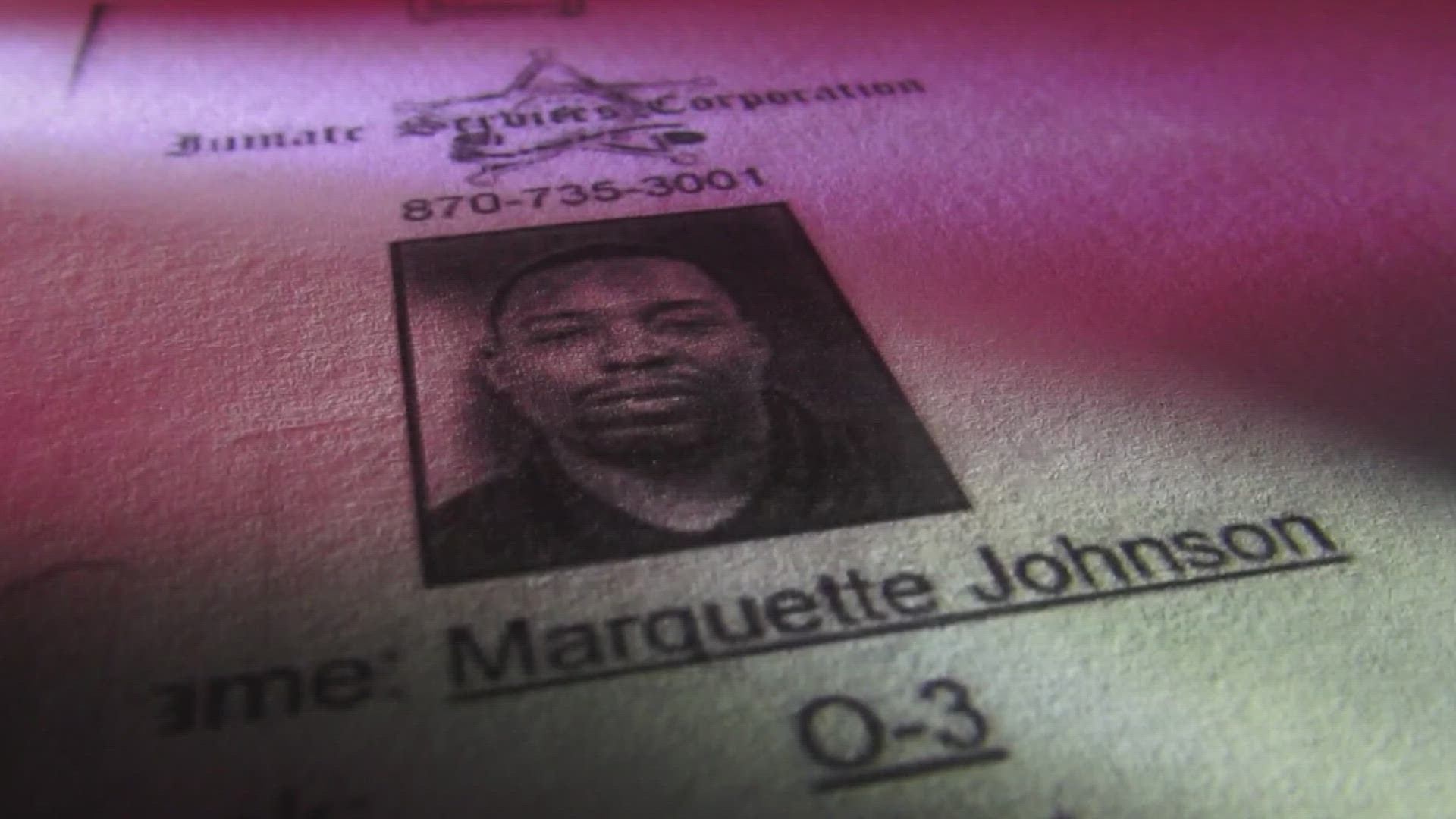

The plan is to provide housing and preventative services to 250 chronically homeless people who will be selected at random from a lottery. 9Wants to Know examined a partial list of those included in the lottery, and found that at least 7 of the ten most arrested individuals could be approached for housing.

The city estimates that jail, detox, arrests and emergency room visits cost taxpayers $7 million annually for just 250 homeless individuals.

Is homelessness a choice?

Police tell 9Wants to Know investigators that many homeless people are often offered resources when they encounter officers – but not everyone is interested or ready for treatment.

“Some of them like being homeless – and they’ll be the first one to tell you that,” Officer Hammack said. “You try to offer them resources and shelter like that, and they will be the first one to tell you they don’t want a shelter. They don’t want to go to a shelter.”

Which means that police and behavioral health workers alike have a difficult challenge to face.

“It’s not illegal to have an addiction. It’s also not illegal to not be engaged in treatment,” Huerter said. “We’ve had other people we’ve offered housing to repeatedly… and they continue to refuse.”

For Tyrone Henry, his feelings are mixed.

“Living out here on the streets like this, this is what people do,” Henry said. “You know what, to tell you the truth,

I think it would be actually a very good thing if I could get housing.”

“It ain’t the best life but, the life that I’m doing, I’m choosing to be this way.”