Considering all of the recent discussion about nuclear weapons, 9NEWS wanted to find out how many nukes the U.S. officially has. You might imagine that information is classified, but it’s not.

And while not all the information is classified, finding accurate numbers and making sense of them has not been easy, even after taking my questions to the Department of Defense and the National Nuclear Security Administration.

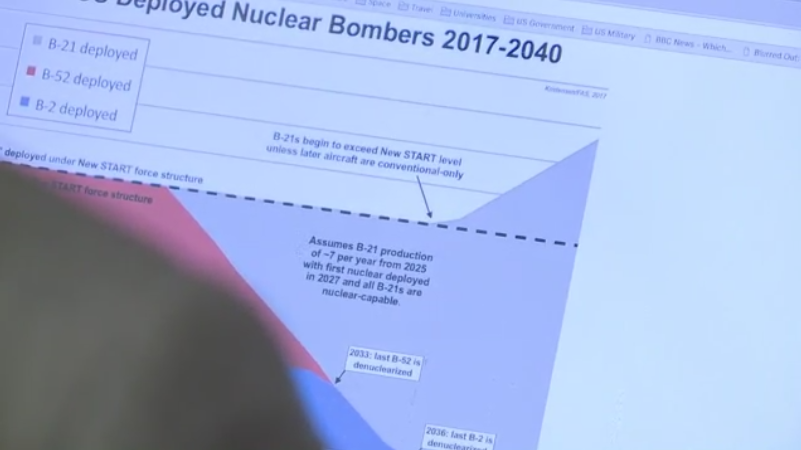

But in my search for the numbers, I found Hans Kristensen, the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, a non-profit based in D.C.

Kristensen has made it his life’s mission to track all the nukes he can around the world. The way he explains it, he has made it his professional business to bang his head against the walls of governments who don’t want to disclose anything at all.

“It’s an enormous challenge,” Kristensen said. “But it’s very rewarding when you see the information used so widely…”

Kristensen and his co-author Robert Norris recently published the Status of World Nuclear Forces.

According to Kristensen’s research, Russia has the most nuclear weapons that are ready to be deployed.

Kristensen and Norris counted 1,950 “deployed strategic nuclear weapons” in Russia. Kristensen explained “deployed” in this case isn’t what people typically think; it’s nuclear warheads that are on ballistic missiles or on bases for heavy bombers.

The U.S. has 1,650 deployed strategic weapons, France has 280.

Kristensen’s and Norris’ research indicates China, Israel, Pakistan, India and North Korea do not have nukes ready to be deployed.

Kristensen says the fact that his research is missing some numbers just shows how hard it is to get information from some countries.

Kristensen has been a firm believer in the public’s right to know and to have an open debate on the subject of nuclear weapons because of where he started this work.

“We were on the front line, nukes were rubbing up against each other around us every day,” Kristensen said about growing up during the Cold War in Northern Europe. “We lived 30 minutes from annihilation every single day and some people thought that was just the way to do it, others thought it was absolutely crazy. I, of course, got sucked into the enormous movement in Europe at the time.”

Kristensen said he’s been tracking nukes professionally for 17 years. He learned how from others before him, who developed the methodology and collected Cold War history information. Today, he publishes work together with Norris.

“The project tries to create what we call the best unclassified estimates of all the world’s nuclear weapons,” he said. “What we’re doing every day is trying to monitor what each of the nine nuclear states are doing to the extent that we can get indications about it.”

Kristensen dismissed the argument that it’s not safe to disclose the stockpile information.

“That has turned out to be complete nonsense,” Kristensen said. “But it has turned out, it has no negative consequences for countries if you know the total numbers.”

“What of course matters is that do you know details about individual weapons how they function, how reliable they are and exactly how would they be used against the target," Kristensen added. "We’re not working in that realm at all. We’re just finding overall numbers.”

He publishes the information online, sharing it in a way the public can understand. He said it opens things up for the government officials too.

“They understand the value of being able to have an accurate debate in the public about where things are heading instead of rumors or worst case scenarios,” he said. “People will spin anyway if they don’t have basic information.”

Kristensen said the declassified statistics he compiles are not only available to the public and journalists but are often used by federal officials whose security clearances can vary.

Kristensen said going up against the secrecy of the likes of Russia and China is worth it.

“In the end it is a democratic struggle because it’s about the right of people to have a right [to] information so they can have an educated debate both about what the nuclear policy should be, and also that they can control; that government officials, governments, in general, are not doing bad stuff,” he said.

Kristensen's nuclear information project is funded by various foundations, some of whom are working to reduce the world's nuclear arsenal.