July 28 marks the 20th anniversary of the Spring Creek Flood in Fort Collins.

Fourteen and a half inches of rain transformed the tiny creek into a raging river, flooding the streets of Fort Collins and the CSU campus.

Now, 20 years later, a student at CSU is working to improve flash flood forecasting. His project could eventually be used by meteorologists across the country.

Greg Herman works out of CUS's Atmospheric Science Building, located at their foothills campus just four miles northwest of the Spring Creek Flood high water mark. His model could help save more lives.

But to understand how his work is moving us forward, we have to take a look back at where we've come from.

On July 31, 1976, flash flood waters rushed into the Big Thompson Canyon. Many people had no warning – and 144 people died.

The Big Thompson flood was tragic, but out of the tragedy, came advancements.

It led to the development of a new flash flood warning prediction system. And since then, the addition of new technology including rain gauge networks, radar, satellite and better forecasting data has helped save lives.

Still, for many scientists, that technology isn't good enough.

"What I would hope a forecaster would do is, start by drawing to these contours,” Herman said.

The 24-year-old PHD candidate at CSU has developed a weather model that predicts potential flooding events two days in advance.

The amount of data this model uses to make predictions makes it different than any other forecasting model currently available. Its forecasts use nearly every ingredient you can think of that goes into a flash flood.

"Probably not everything, but it takes a lot,” he said. “More than any one piece of guidance. It takes the ingredients for precipitation, the actual precipitation from many different model solutions… 11 different ones, and also the local precipitation climatology of the local area and how susceptible one is to flash flooding from a given amount of rainfall compared with another. And synthesizes all of that to give a probabilistic outlook of flash flood potential for the forecaster for one day ahead, or two days ahead of the actual forecast time."

It even looks at how weather models have performed on similar storms in the past and makes adjustments. Greg's model is picking up on flash flooding situations other operational weather models are not.

On September 11, 2013 -- one day before a massive amount of rain fell over parts of Boulder County -- meteorologists across the state were expecting a lot of rain.

"The operational GFS had a very high amount in southeastern Colorado, southwestern Kansas… that was actually very high. But over the Front Range, where a lot of the highest totals were received, it was much too low,” Herman said.

No one saw the 8 plus inches and massive flash flooding that was about to hit Boulder County Thursday afternoon.

Greg and his professor Russ Schumaker recently tested their flash flooding model out to see how it would have performed.

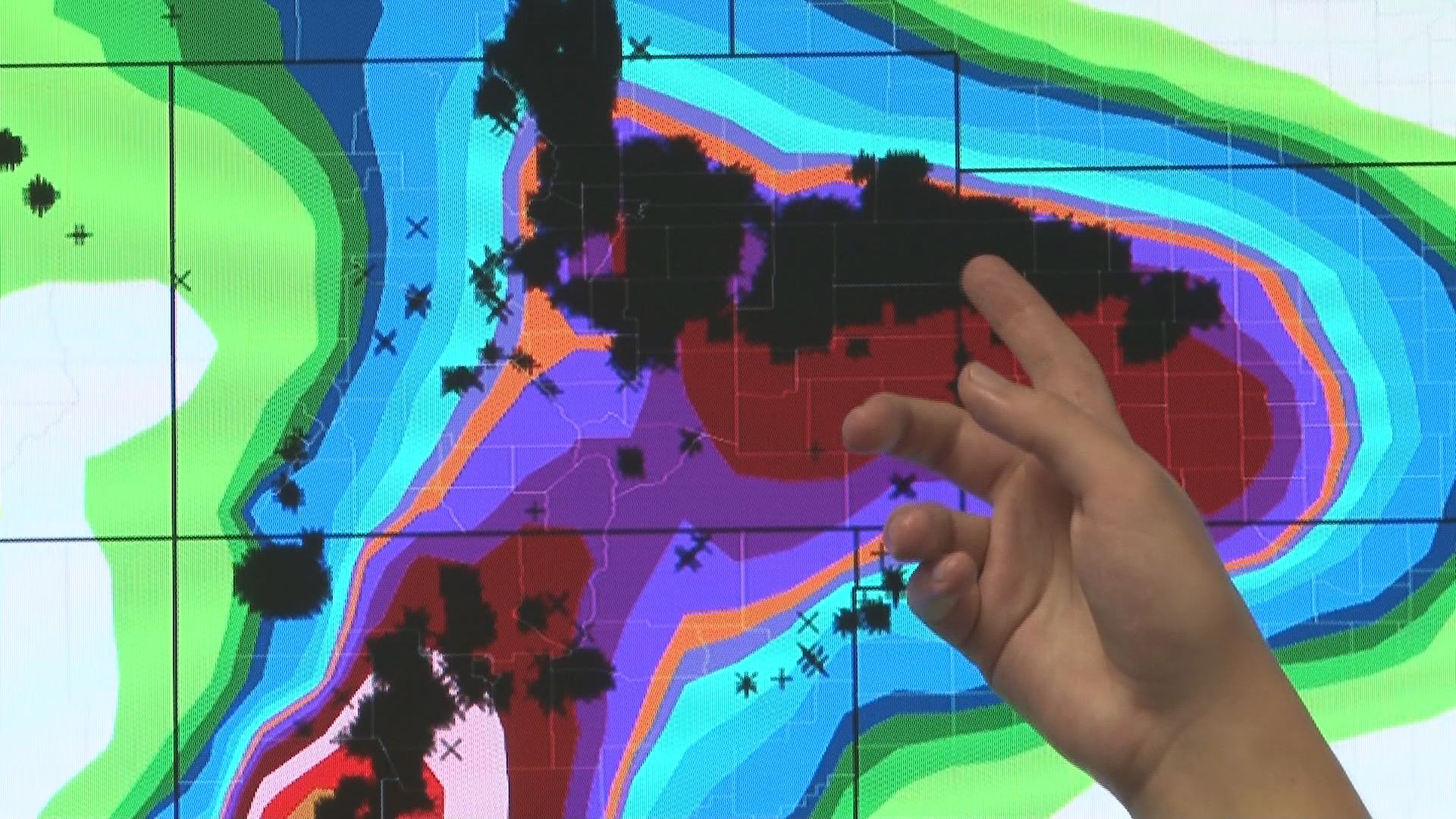

"The contours here, the colors, show the forecast for a few days prior for a 24 hours period during the Colorado floods. And these black points correspond to where that level of rainfall is actually exceeded during this period,” he said.

Their outlook would have been issued September 10 … two days before the flooding happened. And Greg's weather model saw what the others did not: A potentially large flooding event for the Front Range of Colorado.

Greg's model was recently tested by meteorologists at the Weather Prediction Center in Maryland. It received a lot of positive feedback, including excitement about how much time it could save them in the forecasting process.

There are still some kinks Greg and Russ have to work out, but they hope the model will be put into operation by October 2018.