COLORADO SPRINGS — Joanna Fix was gifted intellectually. At age 41, she had earned three college degrees, was the chair of Criminal Justice and Management at a major university and worked as a specialist in Organizational Psychology.

Just eight years later, she no longer teachers, no longer drives and the simple task of loading her dishwasher often leaves her baffled.

Joanna spent years trying to conquer an illness that no one could identify. She struggled to manage her academic life, but found herself getting lost on campus, falling asleep in her work clothes, and finding she could no longer identify or constructively help her students.

Doctors investigated depression, brain tumors, and even looked into Multiple Sclerosis before finally landing on Alzheimer's. Joanna's life had taken a hard turn.

Ask her about her situation, and she will tell you without hesitation: "this can happen to anybody."

"We don't have the luxury of just sitting around and waiting for a solution," Joanna said.

She wants everyone to know the risk we face as a population.

The numbers are sobering by any measure. The Alzheimer's Association says the latest figures show that someone in the world develops dementia every three seconds. In the U.S., someone, usually a woman, gets an Alzheimer's diagnosis every 60 seconds.

By 2050, without a cure, it's projected there will be more than 131 million people in the world living with Alzheimer's.

ALZHEIMER'S COVERAGE | 71,000 Coloradans are living with Alzheimer's | Resources, research and their stories

And, as Joanna can attest, people can acquire this disease at a relatively young age.

Cinnamon rolls were in the oven the day we visited with Joanna in her Colorado Springs home. As she went to remove them, she had to be prompted to use oven-mitts on the hot pan, something she's forgotten to do before.

"You do not want to do this without mitts, because you won't do it twice," Joanna said. "You might, but you'll find you shouldn't."

She knows her memory is constantly suspect, even at this moment as she goes into her kitchen drawer to get something to spread the icing and discovers she can't remember that she needs a knife.

"Uh--O.K.--uh--I don't know what I'm suppose to use in here," she said. "Something--I think I'm going to use this."

She settles on a compromise. A kitchen gadget that has a flat top. She's happy with the selection and she spreads the icing.

"If it gets the job done its good enough," she said.

"All right, so, we'll let that sit," she beams as she elevates the pan so you can see her work. Another compromise bears fruit, in a life full of compromises.

"My firm belief is that people don't want to talk about it," she said. "This is what this has looked like for hundreds of years. There's no cure, no treatment and there's no prevention. Even health care providers are afraid to make a diagnosis because there is no cure. They've just kind of come to accept it."

Joanna wants people to find that unacceptable.

"People should be shrieking, and jumping and having a fit," she said earnestly. "That's how we need to start looking at Alzheimer's disease. This is not something that's just supposed to happen. And by the way, this doesn't just happen to older Americans. I'm one of 200,000 (and growing) people who are getting diagnosed earlier and earlier. I took care of myself. I was a healthy person. I took care of my brain by going to school. If this can happen to me, it can happen to anybody."

The one piece of her life that she has refused to compromise is her relationship with her new partner.

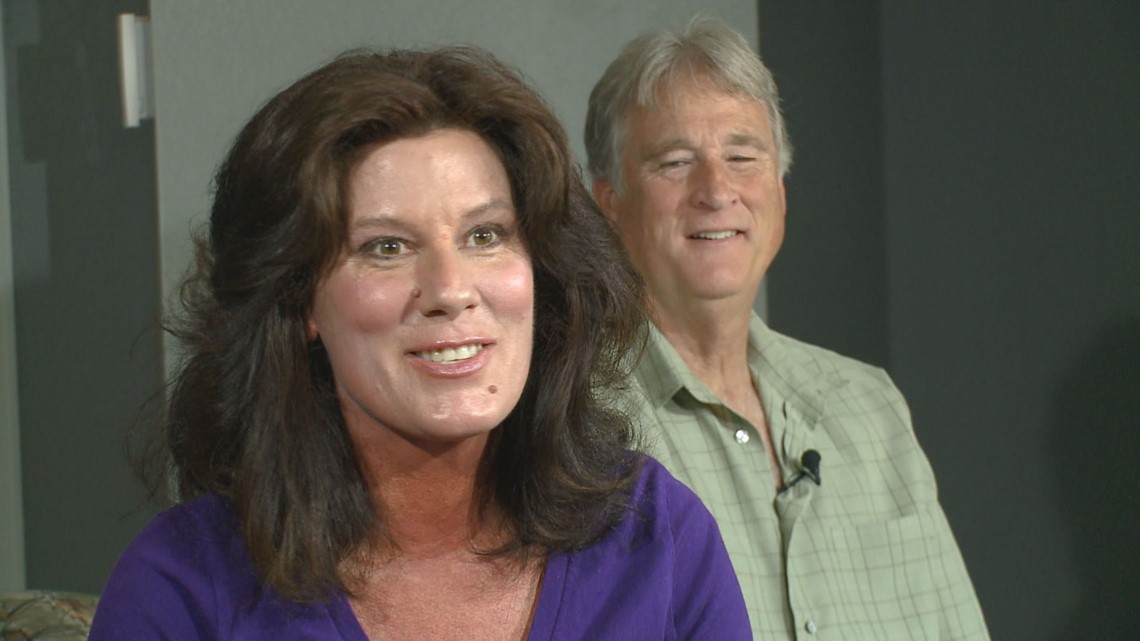

Joanna and her husband Forrest met online. He is her lifeline to calm, to caution and to the order and reason that was so much a part of her old life.

"I ordered him on the internet," she joked. "I mean special delivery right to my front door."

They are still hanging wedding pictures from a year ago. They do most everything as a team these days. Forrest gave-up his career as a chiropractor to be her caregiver and teases her that her compromised intellect, an intellect once the envy of many in her field, is now almost equal to his.

"How not to be able to calculate everything in your head and remember everything verbatim, that's different for her. All of a sudden she's like the rest of us," he laughed, teasing her.

Humor is their coping mechanism.

But there have been unhappy moments, like the snowy, early morning that Joanna became lost simply going to her front yard mailbox.

"As soon as I got there, I just turned around and everything looked different," she said. She no longer recognized her own house.

"So I stood there for a minute and just looked around and the snow didn't help, being in the middle of the night. But I looked at the mail and I said O.K. this must be my house because this is my name, and I walked up the drive and I didn't tell my husband for awhile," she said looking at Forrest with a wide smile.

But there isn't much she doesn't share. On this day it's cinnamon rolls and the hope that people with Alzheimer's start paying more attention to the disease.

"All we have is our moments," she said. "And so, you know, it really doesn't matter what comes after this. All that matters is right now."

She knows right now is all she has and that millions of others are walking the same path.

She's trying to stay positive, despite the fact that like all Alzheimer's patients she is losing her sense of taste and smell and she deals with terrible insomnia and daily confusion.

But more than anything else, Joanna wants people to get mad about it, do something about it and realize that it can happen to anyone.