COLORADO, USA — While the COVID-19 vaccine may be the "beginning of the end of the pandemic" for some Coloradans, others feel more hesitant about being vaccinated.

"I believe the vaccine works. But will I take it? Absolutely not. I'm not going to be at the front of the line," said Brother Jeff Fard, a community organizer and the director of Brother Jeff's Cultural Center in Five Points.

Fard is among those who don't just feel hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine but are outright unwilling to get it.

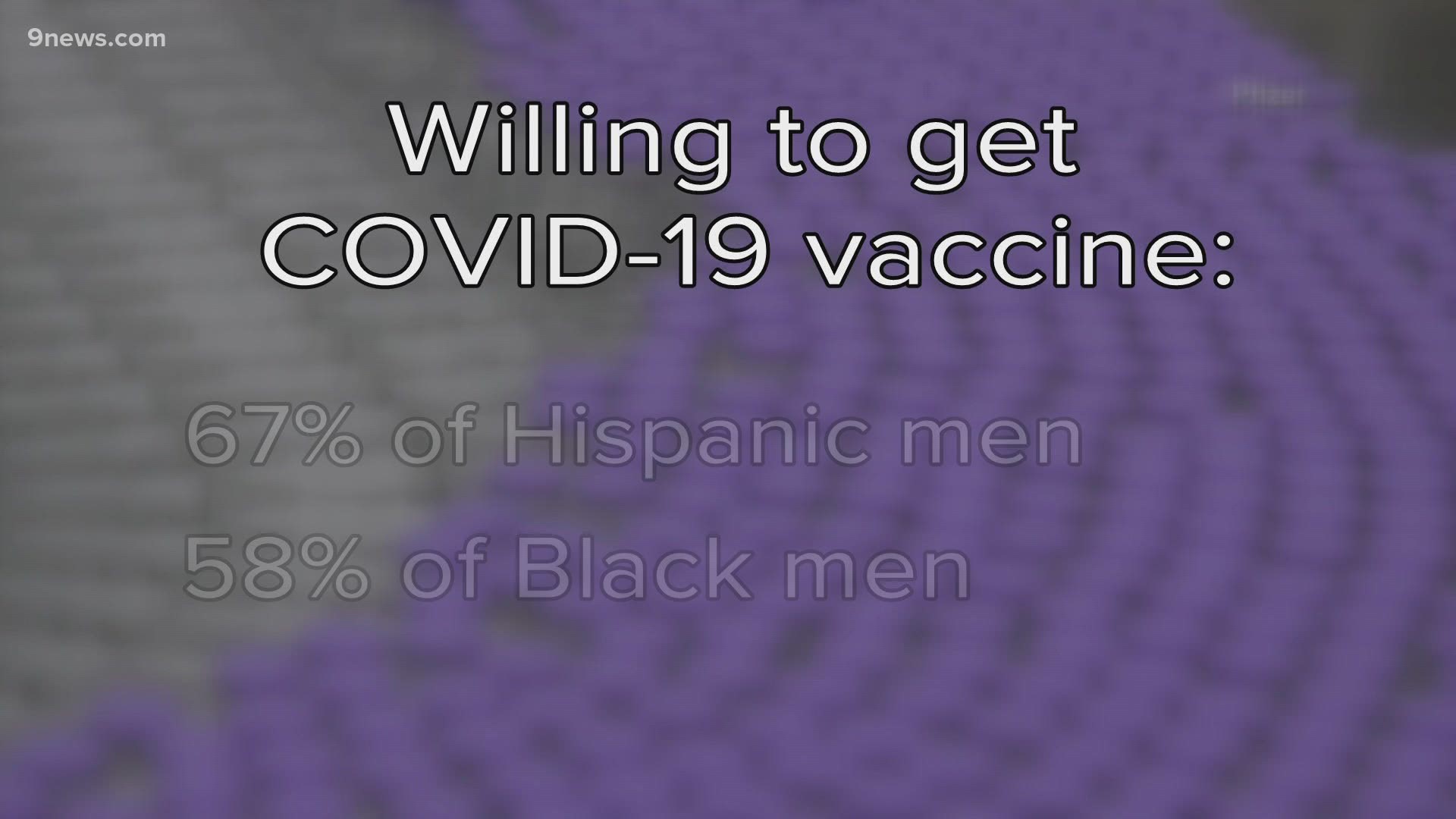

"8 out of 10 Black people will not be in line to take that vaccine initially," Fard said Tuesday, the day after Colorado received its first shipment of Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine.

Fard and 9Health Expert Dr. Payal Kohli agree, the fundamental problem for Fard, and many others who feel the same, boils down to distrust.

"There's a huge amount of hesitancy in minority communities and there are many different components as to why this is. The first is a trust issue," said Dr. Kohli.

"There's a fundamental distrust of the healthcare system," said Fard. "There are reasons that will constantly come up, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment."

The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and was conducted in Tuskegee, Alabama for forty years, from the 1930s to the 1970s. Health officials studied syphilis in Black men for decades while withholding treatment.

"Because of the historical past and the fact that these communities have been used in experiments like the Tuskegee experiment, there's a huge barrier there," said Dr. Kohli.

As a healthcare professional, Kohli sees that distrust play out with many of her patients of color.

"There's a huge cultural barrier. There's a language barrier, there's a knowledge barrier, and there's a trust barrier," she said. "Until we as a society can all systematically work to resolve each of those, we're not going to make as much of a dent with the vaccine in these communities as we have the potential to."

Still, there are other people of color like Ezzie Dominguez, a longtime resident of the Denver neighborhood of Westwood, who are eager to be vaccinated.

"Because we've experienced what this virus has done to our community and to our families, we kind of see the shot as a ray of hope," Dominguez said.

The sentiment from her Latino Hispanic community in Westwood is not how Brother Jeff Fard described the reaction to the vaccine in his community. In fact, it's quite the opposite.

As a cancer survivor, newly in remission, Dominguez is eager to maintain her health. Being from Mexico, she also said she is familiar with the standard use of public vaccines.

"I'm more afraid of the virus than I am of getting vaccinated," said Dominguez, who has suffered a great amount of loss to the coronavirus this year.

"I've already had at least 10 close friends die from COVID, close to 10 family members, and many, many more within our communities who have died of COVID," she said. "Knowing all the suffering, knowing all the debt, knowing all the lack of resources that we've experienced - I speak for me and my family and for all of those friends around me when I say, we are ready for the shots."

Dr. Kohli said the average person can expect to get vaccinated around April, at the earliest. While Governor Jared Polis said it may be summer before the general public has access to the vaccine.

While Dominguez and her family eagerly wait their turn to be vaccinated, Fard said he and many members of his community are just hoping they won't be forced to get in line.

"The larger conversation in the Black community right now is not, if they're going to get the vaccination," Fard said. "They're saying, what if the government makes vaccination mandatory? That's the bigger concern we're hearing about."

Now that a vaccine is here, it seems trust is what needs to be fast-tracked next.

Dr. Kohli and other advocates like Colorado's Vaccine Equity Taskforce plan to work with more hesitant communities across the state to build trust in the vaccine and answer lingering questions.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: COVID-19 Coronavirus