How willing would you be to pay for roads based on the number of miles you drive?

The Colorado Department of Transportation just published its report on a pilot program, officially titled the Colorado’s Road Usage Charge Pilot Program, that it tested at the start of the year. CDOT monitored the distance traveled by more than 100 drivers to compare a pay-by-mile system for roads, and the current system - the gas tax.

There were 147 drivers, from 27 different counties, that enrolled in the pilot program, but only 101 were still participating at the end. I was one of those drivers.

To take part in the pilot program, I had to choose one of three options:

- Odometer Reading: Where I would update my odometer readings through an app

- Non-GPS Enabled Mileage Reporting Device: I would plug a device into my on-board diagnostic port, under my console, and the device would collect information on fuel consumption and fuel efficiency to determine distance travelled. The device would wirelessly report the information Azuga, the California-based company that administers the program.

- GPS Enable Mileagae Reporting Device: This is similar to the device above, except that it is GPS enabled and uses location-based data to calculate total miles driven. Just like the non-GPS enabled device, it wirelessly reports the information to Azuga.

Being the somewhat skeptical reporter that I am, I chose the non-GPS enabled device. I was in the minority. Of the 101 drivers who completed the program from start to finish, 70 chose the GPS-enabled device. I was on of 18 who chose the non-GPS enabled device. Only 13 chose to manually input the data through the app.

Once I plugged the device into my car, I pretty much forgot it was there. The only time I was reminded was when I would get my monthly statements.

According to CDOT, the purpose of the pilot program was not to determine the revenue impacts -- despite pointing out in the report that CDOT estimates it will be behind $1 billion a year over the next 10 years -- but rather to access the technical and operational feasibility of the concept. CDOT added that the current gas tax system cannot meet the state's needs, considering factors like a population increase and electric cars.

"What would it cost us to administer this system, how are we going to handle out-of-state drivers, how do we handle enforcement, those big, broad-based questions -- how do we provide choices for each user, to where they feel comfortable within the system -- those are the big questions that we would have to have answered within 10 years to make this implementable," said CDOT's Metropolitan Planning Organization Manager Tim Kerby.

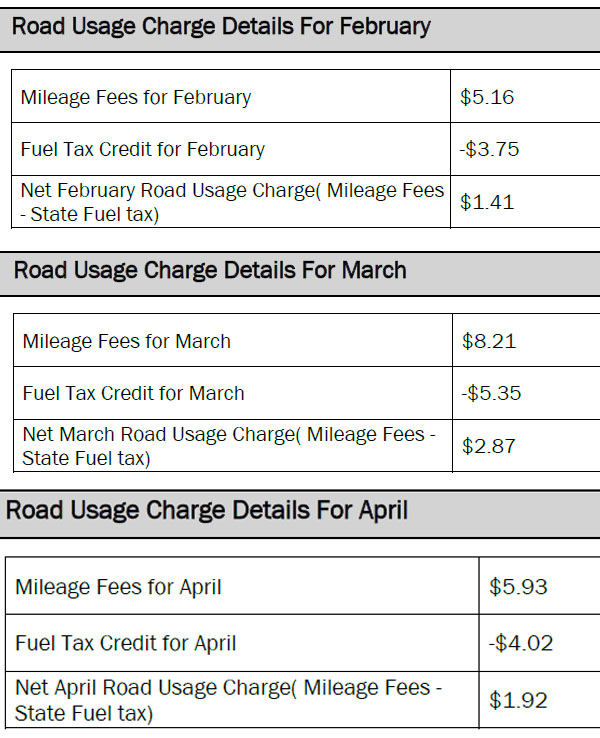

Based on the pilot program simulated billing, I would have owed minimal more per month in a per-mile fee versus the gas tax I pay at the pump.

The billing essentially added the per mile fee and subtracted the gas tax I likely would have paid based on my mileage and determined I would have owed about a cup of coffee each month.

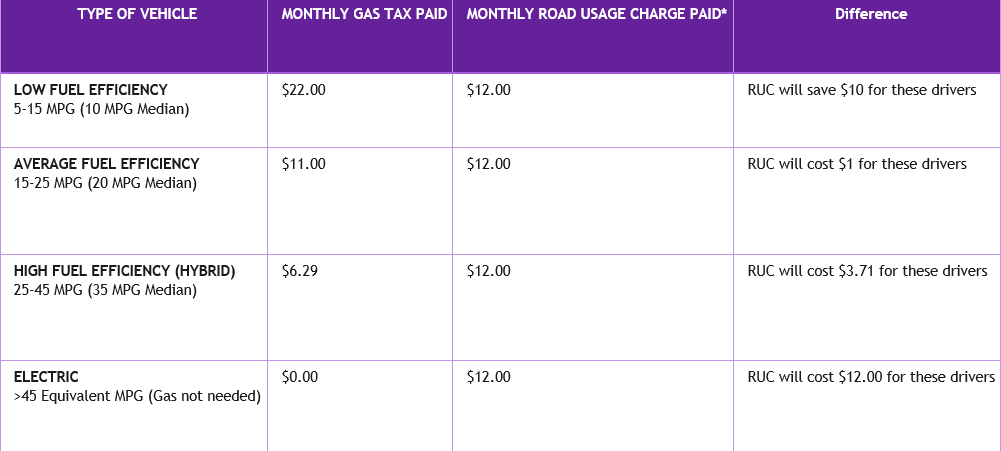

This graph shows how CDOT estimates cost differences for various drivers. For example, a driver of an electric car, who pays nothing for a gas tax now, could pay about $12 a month, assuming they drive 1,000 miles per month. People can find out how their own mileage rates could compare the gas tax system with CDOT's calculator.

Under this system, the state's 22 cent per mile gas tax would be eliminated and replaced with a per mile fee. That, however, would need legislation from state lawmakers.

"If you drive a very fuel efficient car, you're going to end up paying a little bit more. If you drive a very inefficient vehicle you're going to end paying a little bit less," said Kirby. "Whether or not you drive a 1989 Ford pickup truck or you drive a Toyota Prius, everyone under that system is paying the same per mile rate."

Doesn't the system charge more to a rural driver than an urban driver?

"If you're a rural dweller, you tend to trip stack, meaning that you will drop the kids off at school, go to the grocery store, go to the post office, go to the post office and then come back home. Where as if you're an urban dweller, you tend to go to the grocery store, come home, drop the kids off at school come home, go to the doctor's office, etc.," said Kirby.

CDOT called the pilot program a success because of overall positive feedback. The department writes that 91 percent of participants offered strong approval of the program.

However, CDOT's most obvious hurdle, according to the report, could be overcoming privacy concerns. The report lists that convincing the public that data will be protected, and drivers will not be monitored as they travel as "one of the biggest challenges." CDOT says allowing drivers to pick the tracking option they use, as they did for this study, could ease concerns.

Enforcement, cost of implementation, and winning over drivers of electric cars are listed as other challenges.

"For every one question we asked, we got four in return, which tells me that we're doing it the right way," said Kirby. "What if somebody registers a car in another state and drives into this state or how do we manage overhead costs? How would we work with other state agencies?"

These are questions we also wanted answers too, as well as the overriding security concern.

"We never ask ourselves if, in the security field, we ask ourselves when. When a breach occurs, what does that mean?" asked security expert and Metropolitan State University of Denver professor Steve Beaty. "There have been very few places that have not been breached. Even some of the most sensitive and secure places in the world have been breached."

"I have a confession to make, I do not care where you are traveling," said Kirby.

Yeah, he may not, but someone else in the government might. Or maybe even a hacker.

"We built a very solid firewall between the private sector and CDOT. The only thing that could flow through that fortified wall was a VIN number and a mileage measurement associated with it," said Kirby. "We have to rest assured that our private sector counterparts are equally diligent in their efforts to protect the user's information."

He said the data collected by the private company would be required to be deleted after 30 days.

"In the unlikely event somebody was able to hack that system, at most the information they would probably have is 30 days worth of information," said Kirby.