DENVER — One day after a former Minneapolis officer was found guilty of all counts for the death of George Floyd, the House Judiciary Committee advanced a bill to clarify and strengthen certain provisions of SB20-217, the sweeping police accountability reform bill signed into law last year. The bill passed by a vote of 7-4.

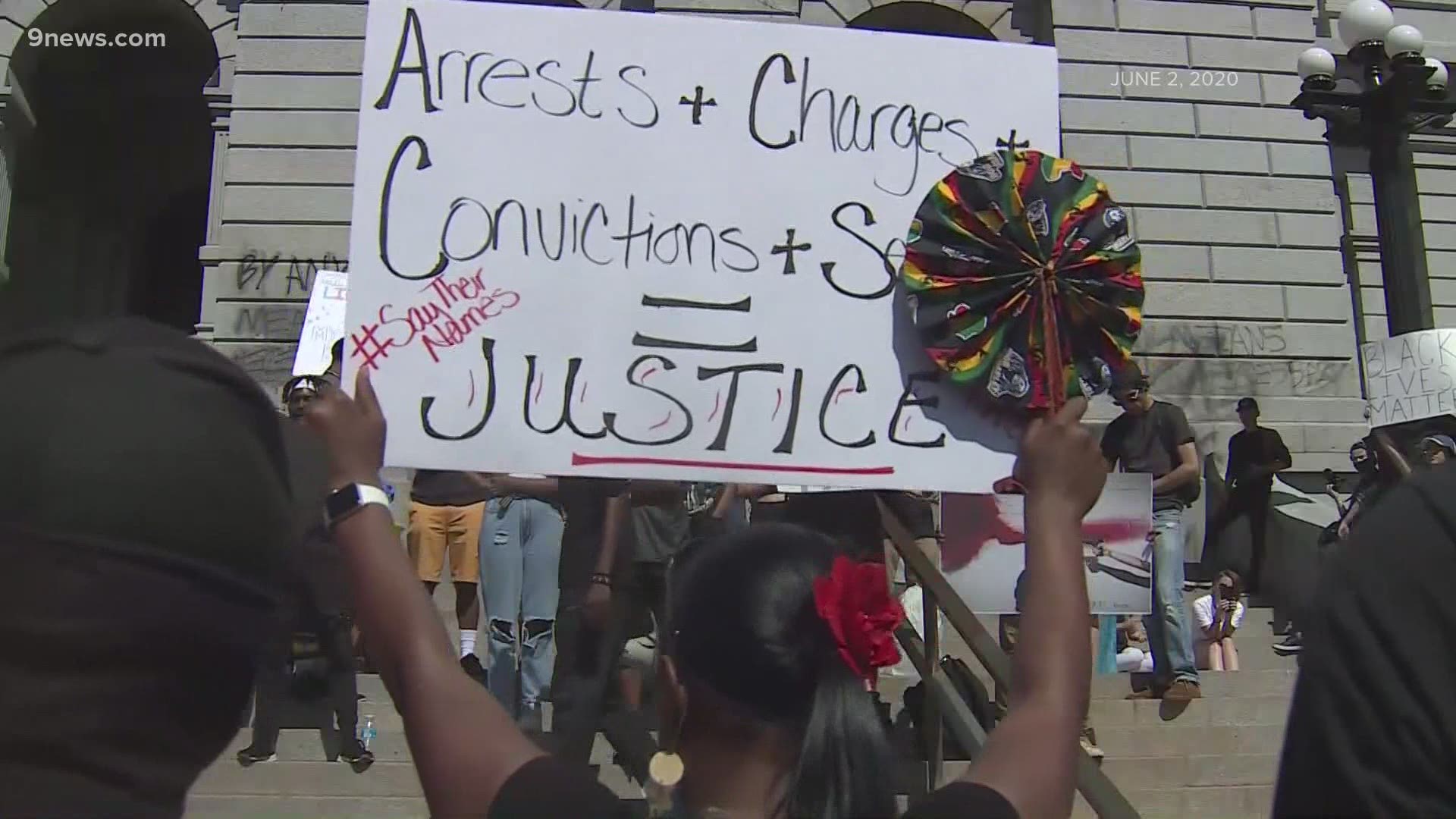

This law was first announced during a rally on the steps of Colorado’s Capitol in early June after a video of Floyd’s May 25, 2020 death sparked protests in Denver and around the world. It was signed into law a few weeks later, and requires body cameras for all law enforcement by 2023, bans chokeholds and holds officers personally liable for using excessive force.

The modifications that are slated to be debated on Wednesday would change the standard for when an officer is allowed to use deadly force and require de-escalation techniques before more physical measures.

"If they can deescalate, if they can build a positive rapport, if they can figure out what is the core issue of what is going on, if they can actually help direct the person to services they need or allow the person to walk away," Rep. Leslie Herod (D-Denver) said.

She said the bill was not written in a way that would “put the officers at risk or in the line of danger” and that it only applies when there is not an imminent threat.

The bill defines de-escalation as: "proactive actions and approaches used by a law enforcement officer to stabilize a law enforcement situation so that more time, options and resources are available to gain a person’s voluntary compliance and to reduce or eliminate the need to use physical force, including verbal persuasion, warnings, slowing down the pace of an incident, waiting out a person, creating distance between the law enforcement officer and a threat, and requesting additional resources to resolve the incident, including but not limited to calling in medical or mental health professionals to address a potential medical or mental health crisis."

Former Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI) Director Ron Sloan is a legislative liaison for the Colorado Association of Chiefs of Police. He is working with lawmakers to provide law enforcement’s perspective on the bill.

"Unfortunately, police officers are confronted with many, many times, situations where there needs to be some exercise of control over the situation other than just a total retreat from the situation," he said. "Sometimes that’s appropriate."

He added that the definition of de-escalation is "not problematic at all."

"What is in need of further clarification, and in need of better understanding, is how you use de-escalation techniques in a use of force situation," Sloan said.

Other law enforcement officials testified today that they have a problem with wording like "exhausted all" when talking about de-escalation techniques.

Chief Clif Northam with the El Paso County Sheriff's Office said that can cause unnecessary hesitation in officers, and create a dangerous situation.

"Use of force situations, they're tense and rapidly evolving situations," Chief Northam said. "And to take the time to consider whether I've thought of every possibility before I take action could really jeopardize the lives of people I'm trying to protect and the officer themselves."

Another change-up for debate includes taking away qualified immunity from CBI and Colorado State Patrol troopers. In the 2020 law, local police officers and sheriff's deputies lost qualified immunity, meaning they could be held personally liable, up to $25,000, for their actions while on duty.

There is another provision about requiring law enforcement to check a misconduct database before hiring or promoting an officer, deputy or trooper. The database would include information if the person has been decertified by the Peace Officers and Standards Training (P.O.S.T.) Board, if they were previously untruthful, fired or resigned while under investigation.

SUGGESTED VIDEO: Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark