For many decades, stone artifacts that had been found in the San Luis Valley, and Great Sand Dunes National Park, had been a mystery.

That was until an archaeologist based in Longmont decided to take a closer look.

"The first time I saw some of these stones was probably 40 years ago at Great Sand Dunes National Park," said Longmont archaeologist Marilyn Martorano. "They were in the museum curation facility and we didn't know what they were."

Martorano worked alongside her colleague, and fellow archaeologist, David Killam.

"About 10 years ago, we actually took a closer look at them," she said.

She added, "We took a real close look with a hand lens, and we looked at other artifacts that are similar like this to try and see what the differences were, but we couldn't figure out why these were so big and so carefully crafted. It just didn't make sense. They are so heavy. Some of them at the park are over two feet long and weigh 10 pounds. So it just didn't make sense that they would've been use to crush or grind."

It took them nearly a decade to determine that the stone artifacts may be some of Colorado's oldest percussion instruments.

Martorano says they got their big break from YouTube right as they were about to give up.

"So we put them back in the cases again, and then a colleague of mine sent me a YouTube video of a researcher at the Museum of Man in Paris. And they had drawers full of these as well, " Martorano said. "The researcher happened to tap on them and realized they are lithophones."

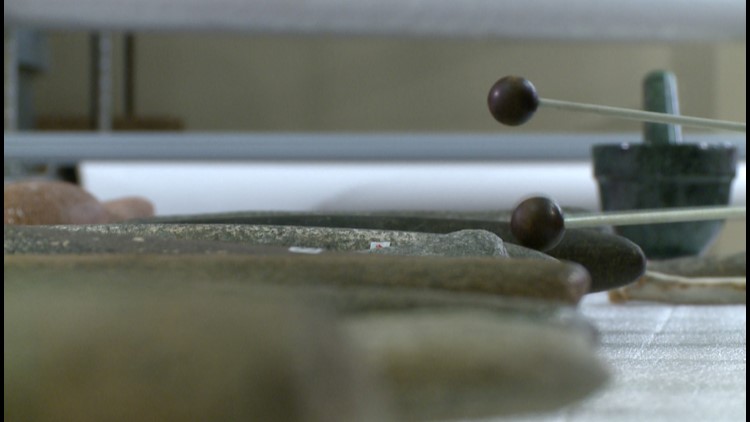

Lithophones are percussion instruments that are made of stone and whose sound is produced by striking.

"I looked at it and I thought 'Wow, that's kind of a crazy idea,' she said. "And I thought, 'Well I ought to at least tap them and see if this could possibly be,' and when I did I was so amazed because they make a real ringing sound and I couldn't get over it."

Martorano and Killam were able to continue their research thanks to funding from the History Colorado State Historical Fund.

"'Litho' is Greek for stone, and 'phone' means sound. So a lithophone is a musical instrument that consists of a purposely selected rock that can be modified, or unmodified, and when you tap on them or rub them with friction, they produce musical notes," said Martorano. "We know that they have to be certain types of rocks."

Martorano presented her findings at a conference in the spring.

She helped many local museums, including History Colorado, learn they actually have lithophones and didn't know it.

"I came back and started literally opening up some of our cabinets looking for these and I found about six potential candidates," said Sheila Goff, the curator of Archaeology and Ethnography at History Colorado. "I called Marilyn to see if she could come down and test them, and sure enough she verified two of them I had found actually are lithophones. We've been collecting since 1879 so they have been here likely decades."

Dr. Holly Norton, the Colorado State Archaeologist, has been closely watching Marilyn's research.

"I'm actually really excited about Marilyn's lithophone research," Dr. Norton said. "It really brings the humanity of prehistoric people to everyday Coloradans who might not think about what living here 6,000 years ago was like."

The next steps, are to learn more about the lithophones.

"I have a lot of questions that remain, that we still don't know about. Where did they get the rock to make these? And how old are they? We really don't know a lot about that because many of these were picked up by collectors, and once you pick something up off the ground if you don't look at the whole context of it -- you can't learn about it," said Martorano.

"My hope is that we can talk to archaeologists and have them hopefully be looking for these when they are excavating or survey. Also, working with museums like History Colorado and looking in existing collections and trying to find some of these."

Dr. Norton says if you see what you believe is an ancient artifact -- DO NOT touch it. Researchers need to look at artifacts in context with their surroundings to learn more about them.

You can report them to local land managers, or call the state archaeologist's office at History Colorado.