DENVER — Three Colorado counties are now telling outsiders they're not welcome.

Clear Creek County Commissioners voted 2-1 on Thursday to close county roads to anyone who does not live in Clear Creek County. Gunnison and Chaffee counties issued public health orders barring tourists.

Clear Creek County Sheriff Rick Albers said his office will initially focus on education and warnings at first. The Sheriff's Office has ordered signage to block certain county roads that lead to popular trailheads.

The resolution voted on by commissioners included ways to check someone's residency.

One was through a driver's license or ID check. Another idea was for the Clear Creek County Board of Health to require the sheriff's office to distribute stickers that residents would put on their car to designate themselves as residents, thus allowed on the county roads.

Colorado used to have that type of Scarlet Letter on every resident's car, but it wasn't a sticker.

Colorado license plates used to reveal more than they do today.

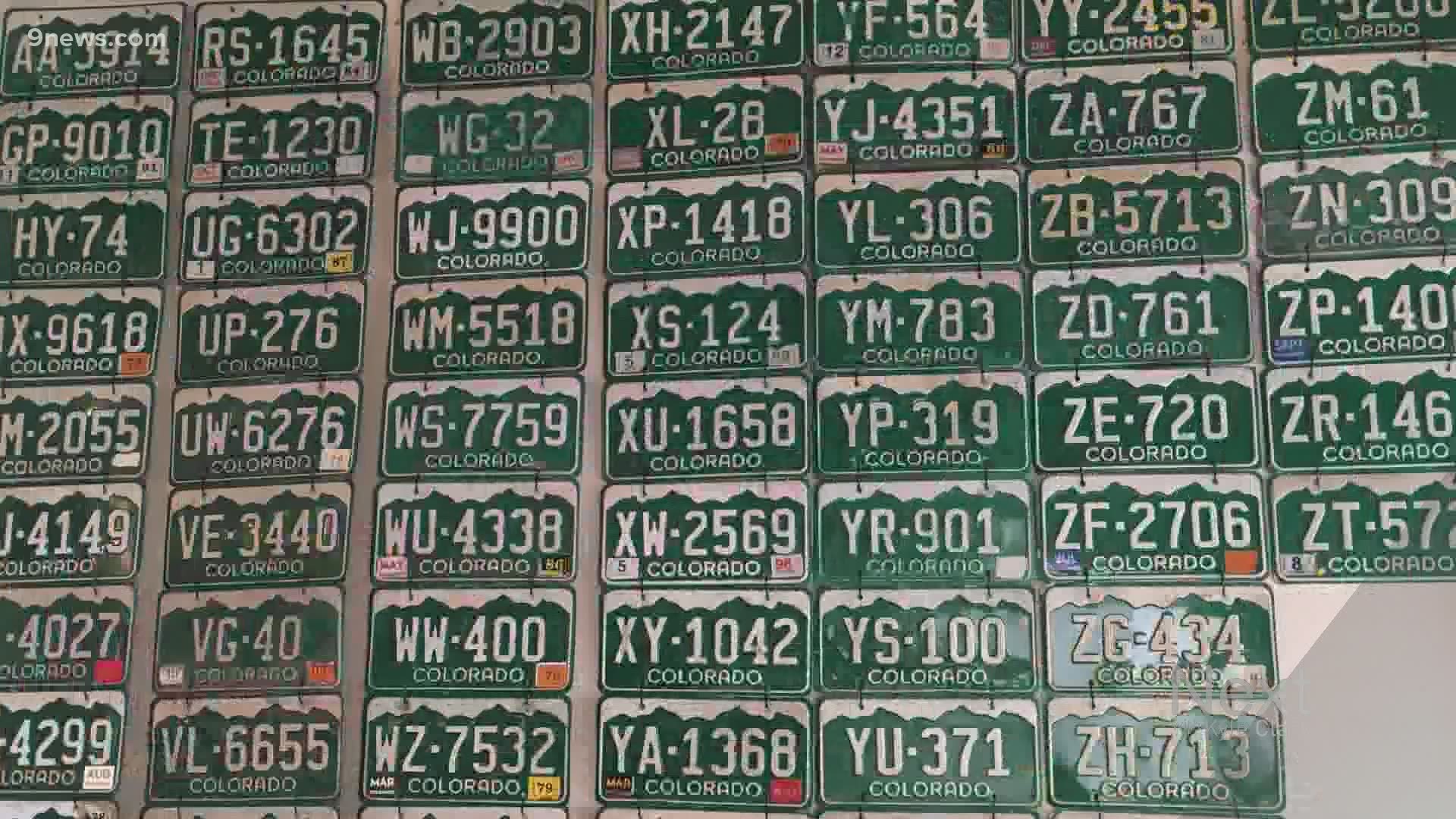

"County specific coding has been around in Colorado since 1932," said Jim Hucks, co-author of Colorado License Plates The First 100 Years 1913-2013.

"It's a great history book. And it also has a lot of statistics about populations and registrations and how certain parts of the state grew," said Hucks.

In 1959, Colorado switched from a number system of license plates to a two-letter, four-number combination. The letters indicated what county you registered your vehicle.

"Denver got the AA, Pueblo got the GP, Arapahoe got the PH, Summit got the ZL, Pitkin got the ZG and Clear Creek got the YY," said Hucks.

An example of each of those license plates is hung on his wall, along with hundreds of others on other walls and in boxes in his garage.

"Started collecting license plates when I was eight years old. I've always liked Colorado license plates," said Hucks. "I love the history of it. It's fun to have a piece of history."

He also has a collection of the "blue denim" license plates from the 90s that took the guesswork out of the license plate codes. The county was printed right at the bottom.

"People loved them. Unfortunately, law enforcement hated them because they had seven characters on them, and they were a little hard to read," said Hucks.

Then in 2000, the current "green on white" plates became the norm, along with any number of specialty license plates, and the coding system went out the car window.

"I have no idea where those plates are from," said Hucks. "When you get out on the road, I have no idea who's from Chaffee County or Gunnison County or Pitkin County or El Paso County. No idea."

Before the legislative session was put on hold last month, a bill that would make changes to the license plate system made it through the Senate, but hadn't started being heard in the house. Among the impacts of the bill, Colorado would go back to issuing "white on green" license plates.

"There are a lot of people who would love to see the green plates come back on the road, in some form. It won't be the two-letter designation that we had for 30 years, 33 years, but it'll be something," said Hucks. "A lot of people would like to see a new issue of general license plates in Colorado, and hopefully they're green with mountains on top."

Even if they do come back, just like the current license plates, you wouldn't be able to just eyeball them and know where the person has driven from. If so, monitoring who shows up in Clear Creek County might be a little easier.

"I see it as a reaction to people not staying home, people still wanting to go to the mountains because they have nothing else to do down here in the Front Range, and it's a problem," said Hucks, a former news photojournalist. "We've been in the news business. We know when there's a fire or some kind of emergency, they only let the locals go up the road, and this is no different."

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark