BOULDER COUNTY, Colo. — Understanding the behavior of the Marshall Fire, which caused so much loss, is top of mind for some researchers right now.

"It was of key interest to many of us because it happened in our backyard and perhaps it was not a type of fire that we were led to expect could happen around here," said Janice Coen, a project scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder.

Coen is also a research scientist at the University of San Francisco, and has been developing simulations of large wildfires that occurred in Colorado and California over the years.

Most recently, Coen developed a simulation of the Marshall Fire, which also includes a simulation of the Middle Fork Fire if it hadn't been put out as quickly.

"And we find that when we include weather simulations, at very fine scales, that is hundreds of points that are only hundreds of yards apart, and we include these effects of the fire and how they change the weather, that we can capture the unfolding and the distinctive features people recognize in dozens of large fire events," Coen said.

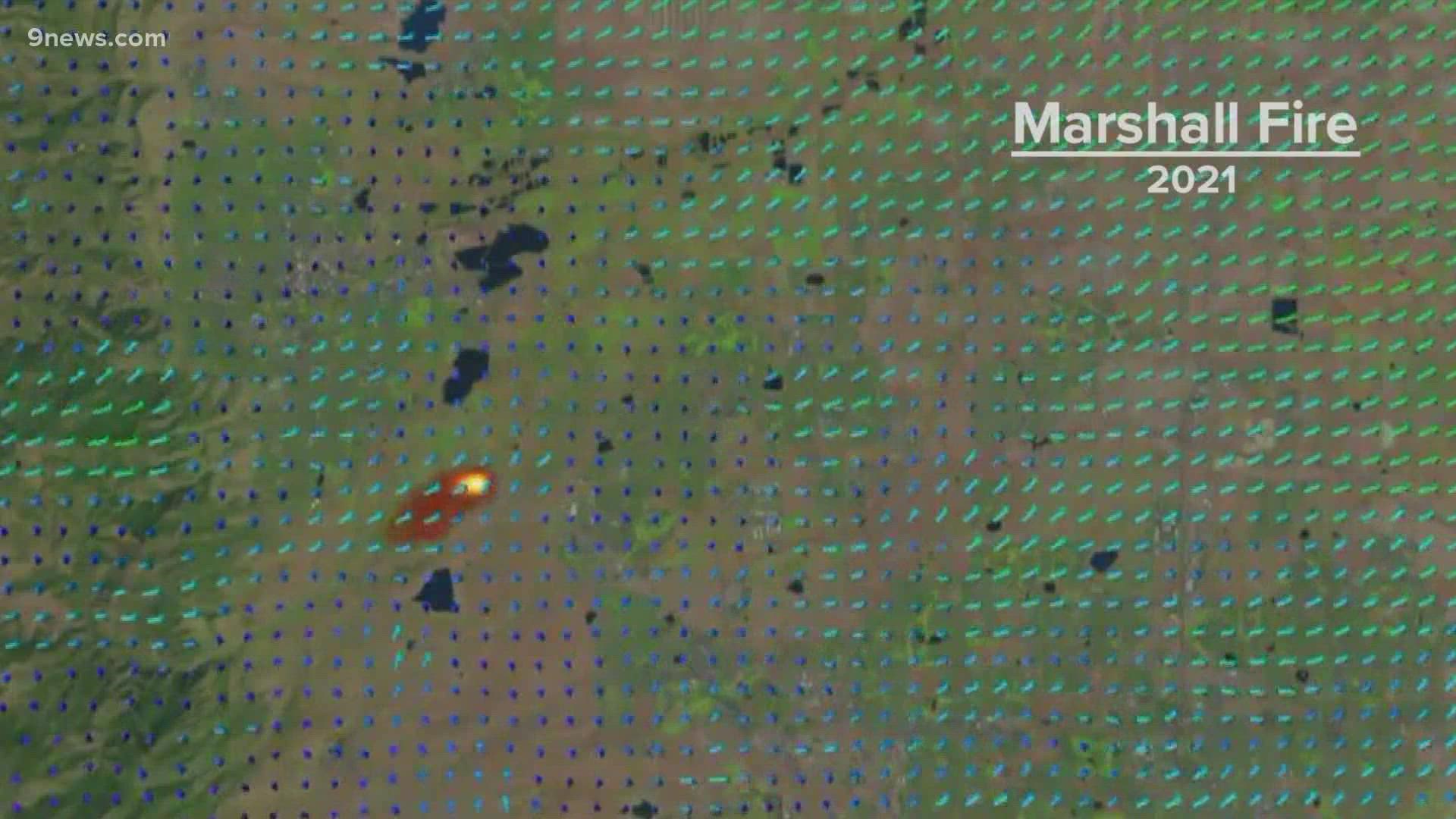

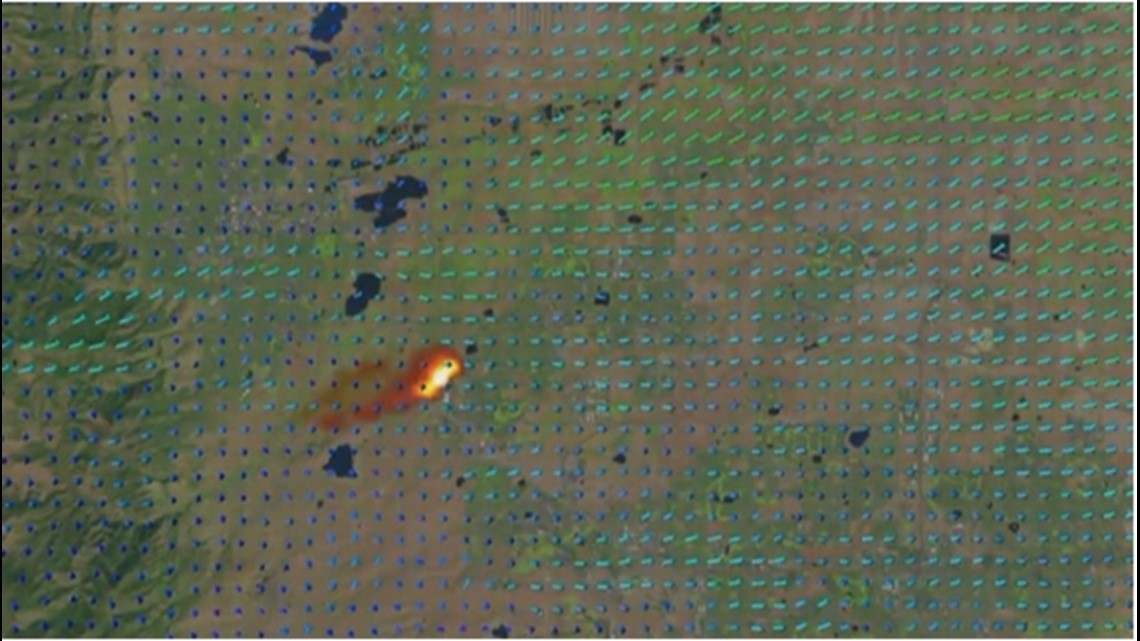

What the animations show

Some of what Coen uses to develop the simulations are computer models that combine numerical weather prediction or weather forecast models, with fire behavior.

"I do simulations in a variety of conditions to understand why fires behave the way they did, how various factors of fuels, what the fuels or how moist they are, topographic effects on weather, how these made the fire behave as they did," she said.

Generally speaking, she models how weather directs the spread of a fire, and how it can create fire phenomena like fire whirls and also how the fire in turn affects the weather.

Other simulations include the Calwood Fire (2020), East Troublesome (2020), High Park (2012) and more.

When it comes to the simulation of the Marshall Fire, Coen described what she was able to observe.

You can view some of those animations in the video above.

"As it spread to the east, driven by our strong, downslope windstorm that day, it spread rapidly, reaching Superior in under an hour," she said. "And then it changed. It became a very different type of fire -- what we call a suburban or urban fire, spreading house to house and the factors that affect that are very different."

What struck her, she says, was that she believes there is some resemblance to the fire events she and others observed in California.

"It was driven by very strong winds. The structure, the temperature structure of the air was statically stable, we would say to a meteorologist. It was resistant to vertical motion, so it clung to drainage, slots in the terrain," she explained. "We capture a very basic aspect of the fire that it spread downstream, somewhat shaped by these small topographic effects on the plains and then changing direction slightly when it came into Louisville."

The shape of the fire, as shown in the animation, formed what appeared to be the shape of an ellipse.

She explained that usually, they don't think of the plains as having topographic effects on a fire.

"But there were changes in the elevation of a matter of maybe 100 meters or so, you know, when you talk about between Marshall and Superior. But there are places aligned with the wind where the road was in a knot up the terrain and whatever the winds were, the fire spread up this knot, and you can see the burning in the base of that knot," she said. "You know, we talk a lot about forest fires, and when you look at these 100 foot flame planes moving rapidly through the forest, there's probably less you can do to save a particular structure. But here it was a matter of keeping something flammable away from this rather low intensity spreading grass fire."

Brighter areas of the animation indicate more intensely burning regions of the fire, Coen explained, namely the leading edge of the "flaming front" of the fire.

Also in the Marshall Fire simulation, it includes the Middle Fork Fire ignition (which occurred north of Boulder on the same day as the Marshall Fire), modeled as if firefighters weren't able to extinguish it as quickly as they did.

Coen wrote that because the fire itself was located in a more consistently windy area north of Boulder, the simulation shows that the Middle Fork Fire may have grown even more rapidly, and approached north Longmont.

"And as it turns out, as bad as that day was, it could have been a lot worse because the middle fork fire was present in winds that would have driven it into and across northern Longmont. So as bad as the Marshall Fire was, perhaps that day could have been a lot worse for Boulder County," she said.

Looking toward the future

Coen explained that she developed this most recent animation to support some other interest from other research scientists in the emissions area and atmospheric chemistry air quality area.

"They were very interested in the evolution of the fire and the consumption of the fuels and the impacts on the regional air quality."

She says the animation should remind people that we're frequently at risk of fast-moving grass fires.

"We're not just impacted by fires when we live in the forest," she said. "I think not that we should panic, but we should be aware of these conditions when they happen. We should have a plan in place for, if not us because we're at work, then our neighbors to evacuate our family, our pets, because we're not going to be allowed back into that area when it's at risk."

In a previous interview with Coen, she explained that what isn't captured well by current operational weather models are the fire-induced winds created by the fire, which she said are often the most dominant winds in certain events.

The research, she hopes, would transition into more practical uses with progress to model fires in the community.

"I get contacts nearly every day from technology providers who want to be able to provide fire forecasts to the public. We're getting better and I think within a decade we should be able to predict not only where a fire is going to go and how fast, but other important factors like where these large whirls are going to form. And I think there's a lot of promise and we should see a lot of development in the next decade," she said in an October interview.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Marshall Fire Coverage