AURORA, Colo. — It’s been a tough few years for healthcare workers.

Stories of burnout include pandemic patient volumes and tragedies, staffing shortages, and mistreatment from patients and visitors.

A new study puts numbers to the stories, and shows how female physicians and doctors of color often experience the worst of it.

Dr. Lotte Dyrbye is the Senior Associate Dean of Faculty and Chief Well-Being Officer at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. She was also part of the research team that published a study this month reviewing reasons for physician burnout, including experiences of mistreatment and discrimination.

“What we’re focused on is physicians being on the receiving end of offensive racial and ethnic remarks, offensive sexual questions, and also sexual advances, and physical attacks from patients,” Dr. Dyrbye explained.

The study, conducted from November 2020 to March 2021, included more than 6,500 physicians around the U.S. The study included experiences during the early days of the pandemic, as well as time before the pandemic.

“About a third of physicians had experienced a patient, or a patient’s family or visitor, saying an offensive racial or ethnic remark aimed at them,” Dyrbye said. “A similar proportion had experienced a sexist remark. And beyond comments, 1 in 5 physicians reported an unwanted sexual advance from a patient, patient’s family, or visitor.”

Female doctors and doctors of color reported the most frequent discrimination and mistreatment. Among female physicians, about 30% reported unwanted sexual advances from patients or visitors.

And about 20% of doctors in the study said a patient or patient’s family refused care because of the way a doctor looked.

“Which is really just heartbreaking,” Dyrbye added.

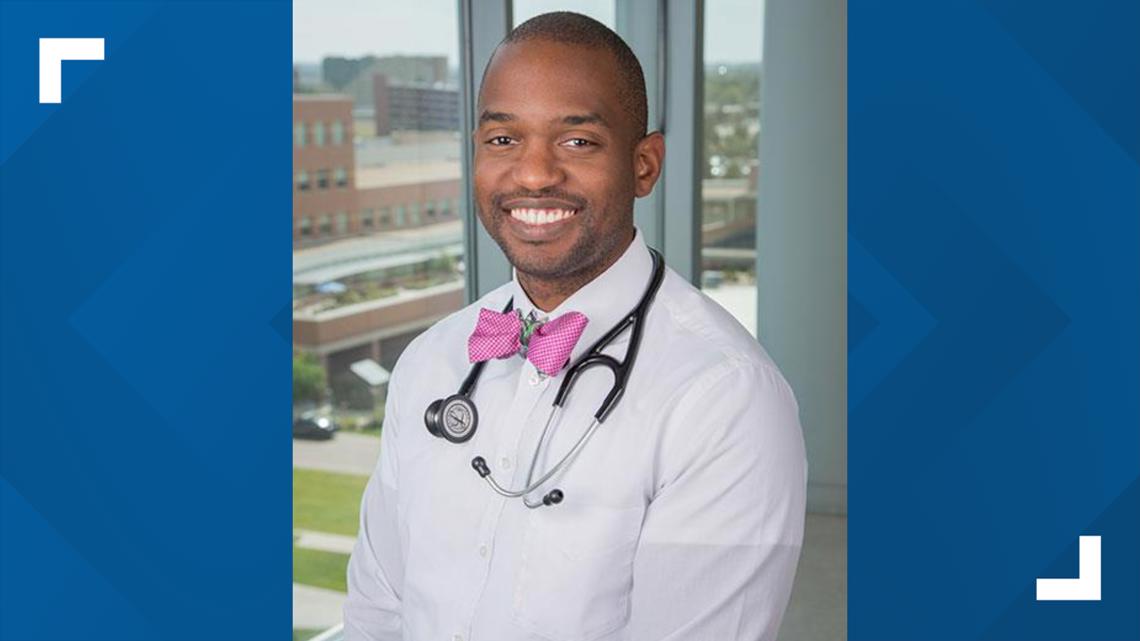

“I’ve seen it all and heard it all,” said Dr. Cleveland Piggott, a family medicine physician and Assistant Professor at CU School of Medicine. Piggott also serves as the Vice Chair of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion for the Department of Family Medicine.

“When my female colleagues are sexually harassed by their patients. When a student who is trying to do their best, and [is] so bright eyed and trying to be there for a patient, and the patient kicks them out because of the color of their skin. And they tell me no one on their team stuck up for them – it breaks my heart,” he said.

“I’ve literally had a patient say, ‘I don't believe what you're telling me. And I'm going to go find a doctor online who actually knows what they're talking about,’” said Dr. Comilla Sasson, an emergency room physician.

“I had another patient interaction, [and] they told me to go back to the border. They wanted a ‘real’ American doctor.”

“It really points to, OK, we need organization approaches to help reduce, the frequency at least, of these things happening to our doctors and healthcare teams, and how better to support people when these behaviors do occur,” Dyrbye said.

"Here we want a diverse workforce, right? And yet our diverse workforce is experiencing behaviors from patients' families and visitors that don’t really align with our values. And that’s then ultimately putting physicians at risk from burnout, leaving organizations, and not caring for patients.”

All three doctors warned about the broader impact of burnout, too: an already existing healthcare worker shortage could get even worse.

“We need doctors. We have a doctor shortage, especially in many different areas, like rural areas, and many specialties – primary care as an example,” Piggott said.

“As a patient, think about how long it takes for you to see your doctor. It’s not because they’re out golfing, it’s because they’re seeing as many patients as they can. And a lot of times when doctors feel overwhelmed, the answer that they choose to do is reduce their hours, that’s the only thing they can do other than just quitting altogether.”

“If we don’t do something now to change the actual environment in which we practice, we’re going to see a very different healthcare situation evolve in the next couple years where it’s going to be really challenging to find people who want to work,” Sasson added.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS