Larry Boeck was a longtime sports journalist for the Louisville Courier-Journal who covered Muhammad Ali for years. He died in 1972. Here is an excerpt from a profile Boeck wrote in 1966.

Some people say that my friend Cassius Clay is an arrogant, overbearing young man. They don’t like his Muslim religion, and they don’t like the things the heavyweight champ has said about the war in Vietnam and about his Selective Service status.

They say my friend hates white men.

Well, if he does, he’s color blind. In a tape-recorded interview during a recent visit home to Louisville he talked about these things. He explained that the vanity he once spouted was “show biz, trickery”—a way to get a shot at the title—the title he is to defend again on Saturday.

The Muslims preach racial segregation; their leader descries white men as “white devils.”

Cassius says: “If total integration would make them happy, the whites as well as the blacks, I would totally integrate. If total separation, every man with his own, would make them happy, I’ll do that. Whatever it takes to make people happy, where they won’t be shooting and hiding in the bushes and blowing each other up and killing each other, rioting. But I don’t think total integration can work.”

Here’s what he says about hate: “I treat everybody right. I haven’t done nothing you could find to show I hate nobody. Hate will run you crazy, going around hating everybody. I don’t have time to hate…”

If my friend, whom some people call the Louisville Lip, pays any more than lip service to the “white devil” tenet, it’s news to me. If he does he ought to find me particularly loathful, for I once told him that the Muslim campaign to establish a nation of its own merely ducks the civil-rights issue. This was about three years ago, shortly after Cassius Clay had defeated Sonny Liston and become champion, Muslim and Muhammad Ali.

“You’re an underrated fighter and you’ll be champion for a long time,” I told Clay then. “As effective as you are in the ring, I feel you’re as equally ineffective out of it because you aren’t fighting for the Negro.”

Clay objected.

“My religion teaches our people should be with their own,” he said.

“Then the Muslims simply are sweeping the whole civil-rights issue under the rug,” I countered.

“I am fighting!” he said. “I’m fighting for the black man, not the Negro. There ain’t no such thing as Negro. I am a black man, and I am fighting for the black man and his right to own his own land and raise his own food and live his own life with his own people on that land.”

Since then I have often thought about that conversation, especially now that Clay has provoked politicians, writers and certain “patriotic” groups with his ill-timed “I ain’t mad at the Viet Congs” when he was classified 1-A in the draft.

Perhaps Clay should have kept his mouth shut, but to me that’s hardly the point. Professionally he has been chased out of the country and must fight abroad because of his remarks. His exercise of free speech has proved mighty costly.

Conversely, when I freely condemned several Muslim tenets he did not retaliate. He did not ban me from his fight camps or cold-shoulder me. Indeed, he went out of his way to be helpful. Perhaps Clay is more democratic than some of his detractors.

Unless, as I said, he’s color blind and hasn’t noticed that I am white that so is Bill Faversham.

When Faversham, one-time adviser for the Louisville Sponsoring Group which got Clay started in the professional ranks, had a severe heart attack, the champion drove all night from Chicago to visit him in a Louisville hospital.

Clay sometimes makes it difficult to peer into this corner of his personality. Yet if this controversial and complex young man is to be understood, his life must be studied.

The champ doesn’t smoke, drink or gamble. Furthermore, he is generous. Having read that he gave a hospital bed to a needy child, I chided him for not having told me about it. It turned out that the story had come from a neighbor’s telephone tip and that Cassius would have preferred that no one “had the story.”

Clay’s friends—and he has more than his critize realize—also point out that, unlike some past champs, Cassius isn’t a thug. He doesn’t get into barroom brawls or go three rounds a week with police. (He does frequently pick up traffic tickets.) He doesn’t beat up old men and he doesn’t throw rocks through windows.

What he has done, of course, is to draw criticism for his offbeat behavior. These are some examples.

He began his professional career with braggadocio, describing himself as “the greatest” and “beautiful,” and in other ways strutting about like a pugilistic peacock. This miffed some people. It enchanted others who saw it as a sports charade. And it befuddled most, who wondered whether Clay was the greatest leg-puller or the most colossal egotist of all time.

He joined the Black Muslim sect. This alienated many fans, even some who enjoyed his “I am the greatest” ranting.

He sought deferment from Selective Service as a conscientious objector. This and later remarks on the subject got his scheduled title fight with Ernie Terrell kicked out of Chicago and eventually the United State. As a result, he fought George Chuvalo in Toronto and Henry Cooper in London. Saturday, he is scheduled to fight Brian London in London. In September, he is to fight German Karl Mildenberger in Frankfurt, Germany.

It was in Toronto after one of his road workouts, that Clay asked me about certain senators’ criticism of Vietnam policy, and wondered why they hadn’t become targets of public wrath, as he had.

“Well, champ, when you speak, you do so as the world’s heavyweight champion,” I began. “You are a big man in sports.”

“Aren’t U.S. senators big men in the world, too?” asked Clay.

“Yes, they are, but when they criticize it’s different. It really wasn’t smart of you to talk about the war as you did with reporters.

“Well, aren’t all those college professors and kids smart?” he persisted.

“Not all of them,” I said. It wasn’t a real answer, and try as I have since that day in Toronto, I still haven’t come up with one.

The champ visits some old haunts on

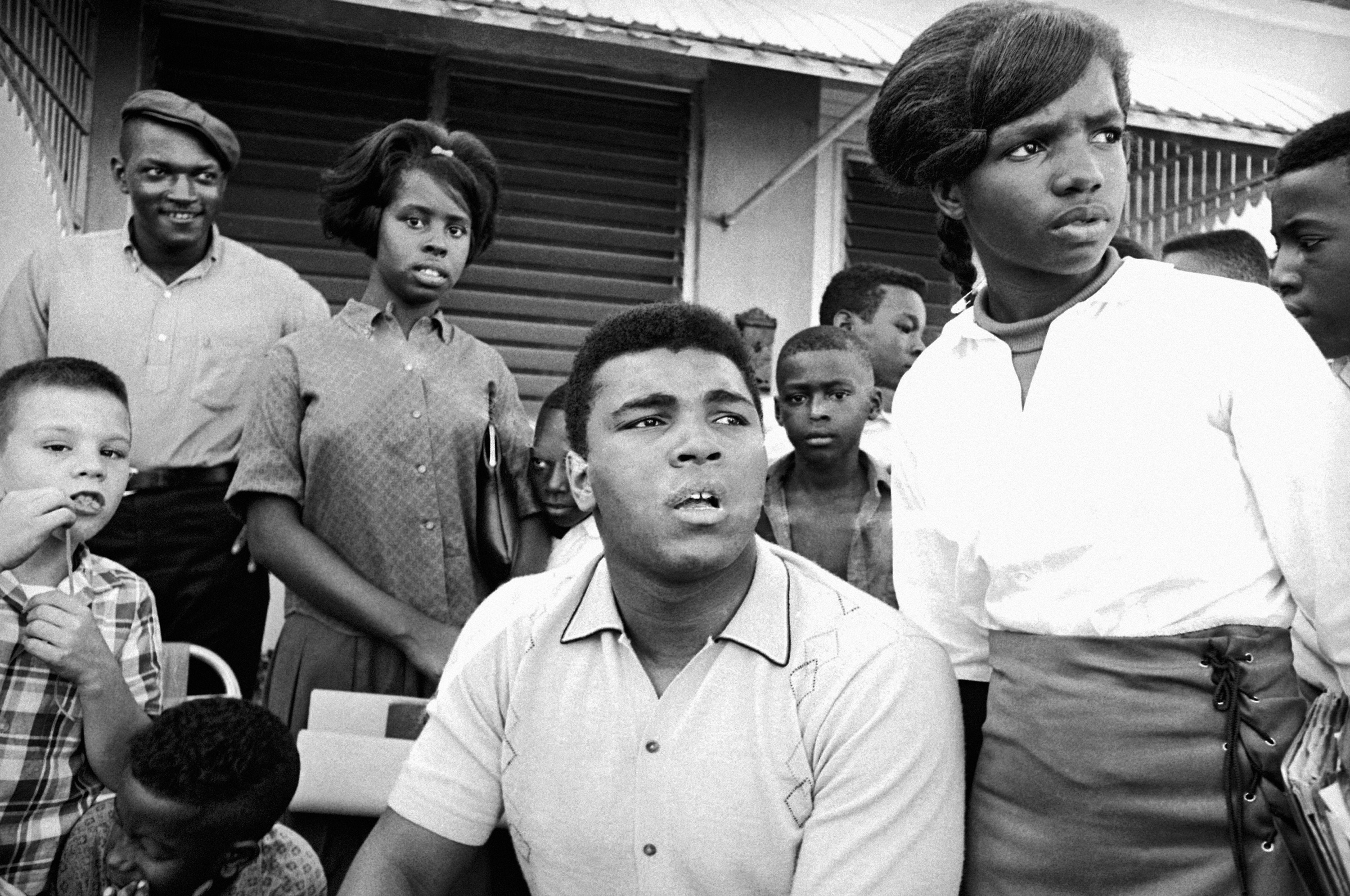

Every now and then, Clay feels the need to return home and visit old haunts. One gets the feeling he still pinches himself to determine if everything else isn’t a dream.

Returning to the old neighborhoods in Louisville’s West End where he lived in a ghetto-like environment seems to recharge his sense of fulfillment.

I picked him up on a hot, sultry day at his parents’ home ear Buechel and he headed toward the West End—insisting on driving my car. He loves to drive—fast and almost recklessly.

Before touring his old neighborhoods, he wanted first to buy some training equipment at a downtown store—heavy shoes and dungarees. He looked first at some motor scooters and boats. “I always wanted a boat,” he said.

I stopped at a golf club display and asked the champ why he never took up golf.

“You’re big, strong and well coordinated,” I said. “Golf would be great recreation for you and you’d be good at it.”

“Golf? No, sir. You lose too much money playing golf.”

He undoubtedly remembered the way former champion Joe Louis, a golf devotee, was taken financially on the links by sharpies. I reminded Clay a guy could play golf and not bet. He wasn’t impressed.

Louisville’s West Side

While Clay shipped, some people turned their heads in disbelief. Could this be the heavyweight champ? It was. Some folks nudged people they were with, pointing out Clay. Others, less self-conscious, asked for autographs.

One of these was B.G. Smith, principal of Mary T. Talbert Elementary School at Eighth and Kentucky.

“We’ve got a Head Start program at our school this summer and the children would die if they found out I got your autograph and didn’t have you come out to see them,” said Smith. “Will you come over for a short visit? It’s just a few blocks from here.”

“I run to everybody else’s city and country,” answered Clay. “I might as well my own.” At the school toddlers and older kids mobbed him. Clay affectionately picked up little, pigtailed girls and hugged and kissed them.

Next he went to Miles Park and looked up jockeys Mike, Bobby and R.L. Cook, three former Golden Gloves champions with whom Clay had campaigned as an amateur. In the jockey quarters, he asked Bobby, “You ever been broke up (injured)?” he asked.

Bobby said that he had.

“You gonna quit?” asked Clay.

Bobby, taken by surprise, said, “Goodness, no.”

“Mmmm, hmmph!” snorted Clay, picking up a baseball glove and starting to play pitch and catch with a couple of riders.

Soon tired of the game, he got behind the wheel and headed for the old Clay homestead at 3634 Greenwood. Kids in the neighborhood shouted, “Here comes Cassius!”

Happy and beaming, Clay jumped out of the car, cuddled the kids, and talked to old neighbors.

“How’s Rudy?” asked an old friend, referring to Clay’s brother.

“He’s got married on me,” answered Clay, laughing.

“You should have stayed married,” said a woman. “Do you good be married.”

“I’m gonna get me one soon,” said Clay.

The next stop was Chickasaw Park, where as an amateur he ran to get in shape. Then he was off toward Grand Street, another former Clay home. At 3227 Grand he spotted an old woman, sitting on her small front porch and rocking.

Again Clay bounced out of the car, calling to me, “Come on, I got somebody I want you to meet. She got a story to tell.”

Mrs. Mabel Ralston came off the porch to greet Clay.

“Want your grass cut today?” asked Clay, grinning happily. “Here’s where I used to make all my money,” he said.

Mrs. Ralston, a cheerful woman with infectious good humor, laughed.

“Cassius and his brother Rudy used to cut my grass to make money,” she explained.

“Who’s doing it now?” asked Clay.

“A little boy down the block who lost an arm,” she replied. “I’ve got to give him something to do.”

“Rudy and me used to cut your grass, front and back, for $1,” Clay recalled.

“Yes, and complain about it,” said Mrs. Ralston. “I’d stand in the kitchen and hear you and Rudy talk in the back yard, and you’d tell your brother, ‘Rudy, we should be gettin’ more than $1 with the high cost of living going up.’”

Clay chuckled and headed for Leonard’s Kentucky Food Store at 3533 Hale. It is owned by Leonard Tucker, a white man. Clay stood out front and shoted. Tucker came out in a white apron.

Clay greeted him warmly.

“I’ve been here 32 years,” said Tucker, “and the Clays have always traded with me. Cassius would run from home to here when his mother wanted something. And he’d run back. Always ran, never walked, even to school.”

“And I’d cut right through here,” said Clay.

The next stop was Gordon Drugs, 32nd and Greenwood. Clay went in and ordered a grape soda.

“I got to get a soda,” he said. “Brings back memories. I’d run and get hot and tired. Drain the whole soda in one swallow. Look here,” he added, pointing at the bottle’s label. “Same make as I got as a kid.”

And so went his tour, meeting new friends, rehashing old times with old friends. Too soon it was over and we headed back to Buechel.

“They won’t realize that they saw me until tomorrow,” he said playfully. “I can’t brag around these folks. Don’t go good. The gals, they just come up, real cool like, and say, ‘How do you do?’

“Next day, they say, real wide-eyed, ‘That was the champ!’”

He flopped wearily in a chair in the living room of his parent’s home.

“Man, I’m tired! I’m done in!” he moaned. Which is something he’d never say on camera. But here he as home. Off camera. Relaxed. Happy. But he was eager to take off again—for New York, London, Frankfurt.

GALLERY: MUHAMMAD ALI THROUGH THE YEARS