BOULDER COUNTY, Colo. — Andrew Whelton is a Professor of Civil, Environmental and Ecological Engineering at Purdue University. He came to Colorado the week after the Marshall Fire to answer questions about water testing. He's back until Saturday to sample private drinking water wells for free.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for context and clarity.)

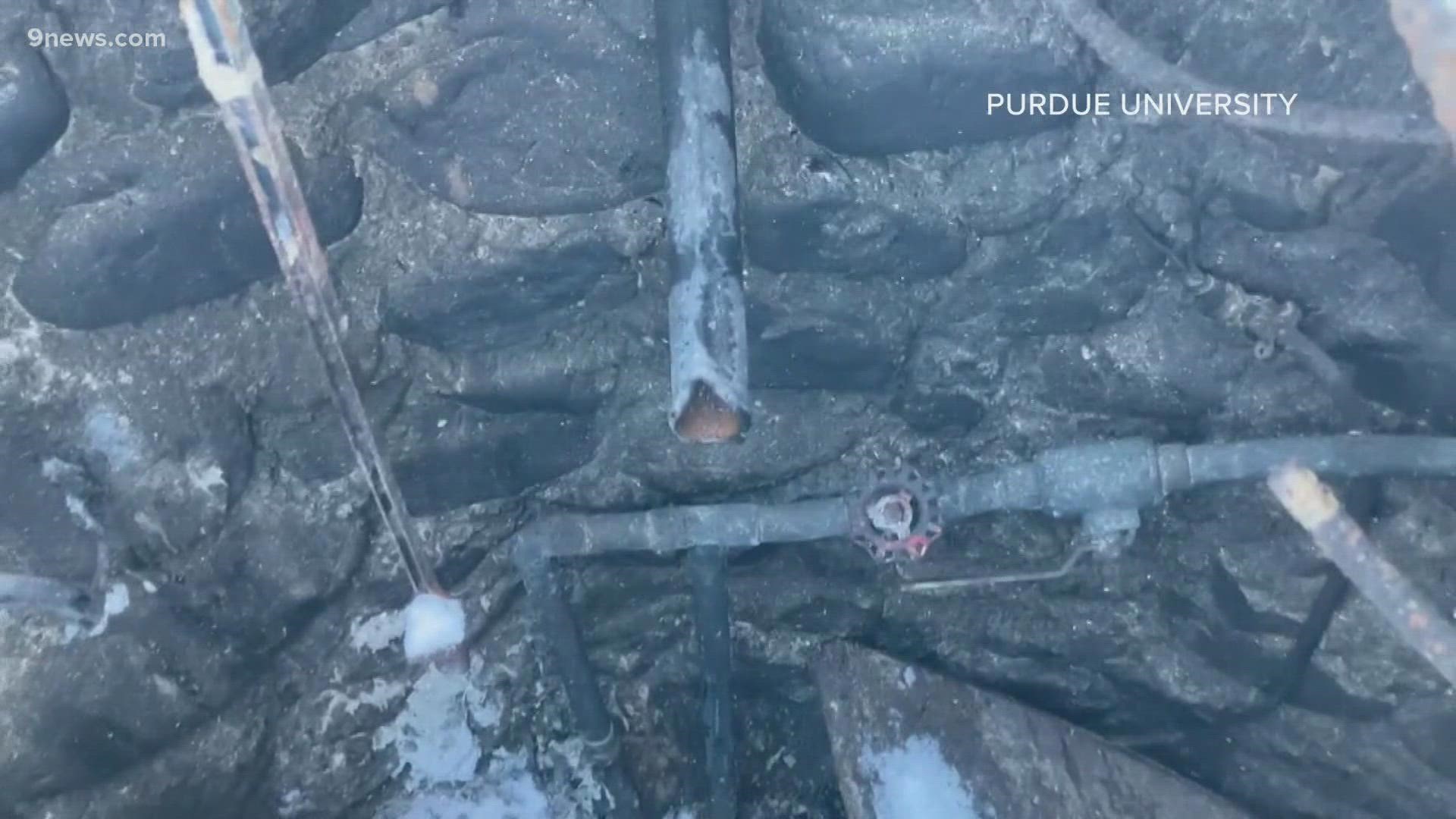

9NEWS: What are these pipes you brought?

Whelton: So these are drinking water pipes that you typically find for buried water service lines that connects the water main to the street to the middle of the house or inside buildings. Many of them are metal, but some are plastic, and the plastic ones are the ones that generally don’t survive fire. Or even if they do survive fire, then can become contaminated, and after you put clean water in there, they can make that clean water unsafe.

So when you see plastic, you’re worried?

Whelton: When we see plastic we know they are way more susceptible to heat damage. We’ve already seen it in private wells where the plastic pipe looked like it was singed and it transfers water from the private well to the home. And so that’s something that we’re interested in making sure that that private well owner has their well tested correctly.

If you see metal, are you still worried?

Whelton: When homes burn, sometimes what happens is the water system loses pressure. And the air and soot and maybe plastic materials can be sucked into even metal pipes, and then as they cool down, they can actually stick inside the pipe. And so just because you don’t have plastic service line or well pipes and such doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re free of contamination. You have to actually test it to determine if it's there.

What do you do in terms of disaster work?

Whelton: Historically I’ve gotten involved in man-made disasters like chemical spills or wildfires. In certain cases I was called in because it was just a mess. People weren’t testing correctly, people were getting sick, kids were getting sick, people were going to the hospital. And the individuals and government agencies making decisions about what to test for didn’t necessarily know what they were doing.

What are some other disasters you’ve helped with?

Whelton: We were called into West Virginia after the 2014 chemical spill. The water smelled like black licorice candy for 350,000 people. They couldn’t get rid of it. And it was primarily because they didn’t understand what was in the water.

After the 2017 Tubbs Fire in California, they had hazardous waste contamination in their water system. Months after listening to government agencies about how to get their system back to safe use, they couldn’t figure it out, so they called us, and we said, "well, that’s because you have plastics in certain parts. You need to just rip them out and start over." So they did that.

After the 2018 Camp Fire, we realized the state was not reading their lab sheets correctly and there was a lot more than benzene in the water. We helped the state and the county figure out how to test. We helped private well owners.

How did you end up here?

Whelton: We got called in early the week after the fire. The city of Louisville called on a Wednesday afternoon at 1:30 and asked me to be on a plane by 5 here. So I came in the week after the fire and helped them figure out what they needed to test for and where they needed to test. I also liaised with the health department and the state health department.

What do you see as the biggest issue with this disaster?

Whelton: From a water perspective, private well owners are on their own. The state does not have the financial resources at the present time to support them to do the testing that’s needed. After the 2021 wildfires in Oregon, Gov. Kate Brown authorized money to help the communities that were affected to do well testing. That’s probably going to be one of the biggest issues.

How much money would be needed to help?

Whelton: Brown authorized, with legislative support, about $200,000, but a lot more well owners were impacted by their fires. It would be less costly than that.

If someone pays for this themselves, what is the cost?

Whelton: The cost can range between $600 and 800 per sample. You can take one sample of your well, but if your pipe between your home and well is impacted, like you lost pressure, then you have to take another sample there, and then potentially you may have to take a sample inside your house--one or two. So we’re talking potentially thousands of dollars worth of testing.

What chemicals should people be looking for?

Whelton: So after wildfires, there’s like 30 chemicals over the last five years that we’ve figured out typically show up in the water systems, and so you have to look for those. You have to tell the laboratory, 'I want these chemicals looked for.'

Have you been in contact with Gov. Jared Polis?

Whelton: I called him. Left a message. Tweeted. Historically that’s how I’ve interacted initially with governors. That’s how we made contact with the governor of West Virginia and helped them out. Coloradans are really lucky to have such caring and forward-leading people. In the disasters I’ve been to, I haven’t seen anything this proactive before. From a water perspective, there’s some things that need to happen, and that’s what I wanted to talk to him and his staff about.

Polis' office said in an emailed statement:

"The administration appreciates Purdue University’s efforts to work with the county to offer free testing during their proposed window (1/23-29) and the state is evaluating additional free well testing after that initial window has closed. If your water comes from a private well and your home/business sustained damage, have your water tested. We encourage people to test and we have a list of certified labs that people can choose from."

That list of certified labs can be found here: cdphe.colorado.gov/dwlabs

Why do you do this?

Whelton: My experience with the U.S. Army helping deployed units understand if the water’s safe where they are. Getting called in any given scenario made it real that there are people that need to know, is the water safe? What’s in the water? My experience in West Virginia, going into people’s homes, meeting mothers who just had babies where their children were bathed in the contaminated water and asking me questions had a visceral kind of emotional reaction that people need help in these situations.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark